Review: ‘Logicomix’ by Doxiadis, Papadimitriou, Papadatos, and Di Donna

Logicomix: An Epic Search for Truth

Written by Apostolos Doxiadis and Christos H. Papadimitriou; Art by Alecos Papadatos; Color by Annie Di Donna

Bloomsbury, September 2009, $22.95

Ever so often, there’s an object lesson that proves the saying so many of us like to make: that comics aren’t just for adventure stories, that they’re suitable for any kind of story. If we’re lucky, those paradigm-breakers are also really successful – and [[[Logicomix]]] is both of those things. It’s a major graphic novel on an unexpected topic – the life of Bertrand Russell, with a strong emphasis on his work attempting to create a solid foundation for mathematics, and thus all of learning – and it’s been quite commercially successful, alighting on bestseller lists occasionally and moving a surprising number of copies.

Logicomix, though, is also a piece of metafiction – the first character we see, on the first page of this graphic novel, is co-author Doxiadis, talking to the reader about this very story, and introducing us to co-author (and logician/computer science professor) Papadimitriou, and then to the art team, Papadatos and Di Donna, and their researcher, Anne. The authors and illustrators return to the stage – very literally, in one case at the end – several times in the course of the graphic novel, mostly to explain the details more carefully, and, occasionally, to lightly debate with each other about the meaning and import of the story.

After that bit of throat-clearing, Logicomix starts up in earnest…with another frame story, in which Bertrand Russell arrives to speak on logic at an unnamed “American University” on the eve of WWII, in 1939, and finds himself interrupted by protestors who want him to stand up unequivocally for pacifism, as he did during The Great War. Russell instead launches into his speech, which forms the narration boxes – and occasional interludes – for the rest of the graphic novel, as the panels depict first Russell’s youth and then his early mature years, as he worked on the foundations of logic.

Of course, we all know that comics can be for adults now…but

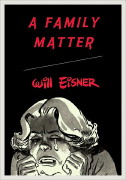

Of course, we all know that comics can be for adults now…but Will Eisner has a towering place in the modern comics field

Will Eisner has a towering place in the modern comics field

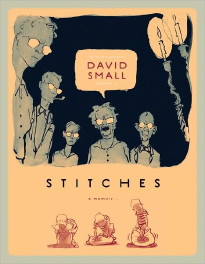

The impulse to anecdote is ubiquitous in mankind; we all

The impulse to anecdote is ubiquitous in mankind; we all