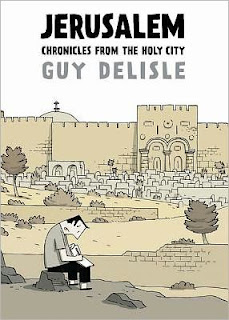

REVIEW: “Jerusalem” by Guy Delisle

Everyone has their niche, their two inches of ivory that they work over so closely with a fine-haired brush. Some niches are larger than others — project manager, superhero artist, war apologist, social novelist — but they all bind, more or less, around the edges. Some artists fight against that niche, and some embrace it.

Everyone has their niche, their two inches of ivory that they work over so closely with a fine-haired brush. Some niches are larger than others — project manager, superhero artist, war apologist, social novelist — but they all bind, more or less, around the edges. Some artists fight against that niche, and some embrace it.

Guy Delisle is a cartoonist — originally Canadian, though resident in France for some time — whose niche is creating books about the strange foreign cities he finds himself living and working in. First was Shenzhen (see my review), about time spent working as an animation supervisor in that Chinese city. Then came Pyongyang

(see my review), in which the same job took him to that very odd, constricted North Korean capital. And then there was Burma Chronicles

(see my review), by which point Delisle had transitioned to a full-time long-form cartoonist, and was accompanying his partner (a Médecins Sans Frontières administrator) to the capital of the country that wants the rest of us to call it Myanmar. (Somewhere in between, he also published two books of unsettling, mostly sex-role related cartoons — Aline and the Others

and Albert and the Others

— which I also reviewed.)

Delisle’s work typically has a crisp, clean line — as one would expect from an animator working in France — with a good eye for detail and enough description and narration to allow the drawing to be simple; he doesn’t try to cram everything into either words or art.

Recently, Delisle’s wife was posted by MSF to Israel for a year, and so, eventually, that experience turned itself into his most recent book, Jerusalem. It’s larger and more diffuse than those previous books, over 300 pages long, and filled with lots of small stories about Delisle’s and his family’s life in a Palestinian neighborhood in East Jerusalem. (And that location is the first manifestation of what will be a major concern of Jerusalem: borders, both physical and mental, and how they interleave themselves, through walls and checkpoints and bus routes and roads and prejudices.)

Jerusalem doesn’t grapple directly with the legitimacy of the Israeli state, or of its treatment of Palestinians (or, conversely, with the actions of Palestinians and others against Israel), making it feel a bit politically naive at times. (Reading it in tandem with Sarah Glidden’s How to Understand Israel in 60 Days Or Less — see my review — would be interesting; Glidden was in Israel for a short time, on a tour, specifically as a tourist on a heritage tour designed to make her intensely pro-Israel, and intensively questioned the Palestinian situation, while Delisle lived in Israel for a year, mostly among vaguely pro-Palestinian expatriates, and lives the physical discomfort of the occupation without engaging with it on a theoretical level.)

Delisle’s job — besides writing books like Jerusalem — is a house-husband; he had two small children during that year, and just taking care of small children (even if they are in day-care part of the time) is massively time-consuming in ways that it’s hard to describe. When you wake up with a toddler, you get through the day somehow, and then wonder, at the end, what you actually did during the last sixteen hours. So Delisle isn’t as free to move around this year as he was in Shenzhen and Pyongyang — but, then again, those were shorter trips, so he had more time to immerse himself in Jerusalem (and, before that, in Burma), more time to live in those places rather than just passing through them.

Jerusalem is a discursive, rambling book, equally about daily life as an expatriate in East Jerusalem and the physical problems of just moving around so militarized and controlled a country [1] as it is about Delisle’s continuing attempts to sketch and draw and work on his cartoons when he has time away from his young children. It’s a long, looping story, circling back to those same few concerns — time to sketch, physical access, which day things will be open — and is more obsessed with time (the right day, the right time of day, enough time to do something while the kids are in day-care) than one would expect. Throughout, Delisle is an interesting and thoughtful guide to Israel, showing us the things he did and saw and thought, and what it was like to live in that place for that time. I expect some people will be unhappy at Delisle’s take on the Israel-Palestine situation — people on either end of that argument, because as much as he engages with it, he’s somewhere in the middle — but that’s an occupational hazard when you create books about your time in odd, contested, unlikely places. Delisle is always honest, and shows us what he sees and feels: you can’t ask for more than that.

[1] His partner was posted in Gaza for most of this trip, and the one crossing into Gaza is more tightly controlled than any other gate in Israel.

Related articles

- Jerusalem by Guy Delisle (antickmusings.blogspot.com)

- Delisle jumps from Pyongyang to Jerusalem (lfpress.com)

- Guy Delisle’s Jerusalem: Not Just Another Brick In The Wall (telegraph.co.uk)

There have been a lot of parodies/mash-ups of that particular Liam Neeson soliloquy, but

There have been a lot of parodies/mash-ups of that particular Liam Neeson soliloquy, but

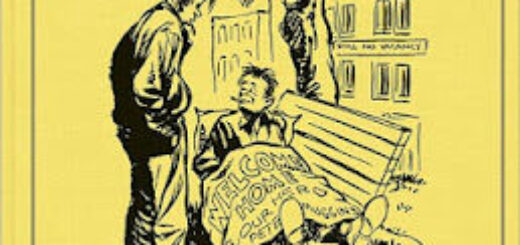

This book — collecting the cartoons Mauldin created for syndication from July of 1945 through the end of 1946 — cannot be fully appreciated by just reading those cartoons. Luckily,

This book — collecting the cartoons Mauldin created for syndication from July of 1945 through the end of 1946 — cannot be fully appreciated by just reading those cartoons. Luckily,  Handler has written for younger readers before: under his pen-name

Handler has written for younger readers before: under his pen-name

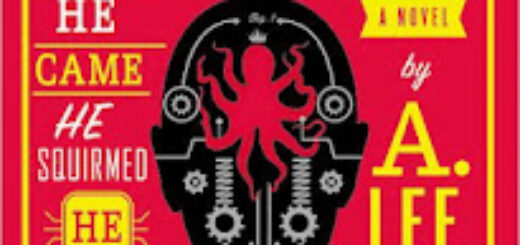

It is simply impossible to declare a novel “not funny.” Humor is so personal that all any person can really do is declare whether he laughed or not.

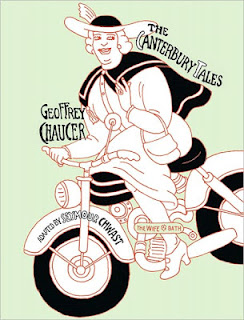

It is simply impossible to declare a novel “not funny.” Humor is so personal that all any person can really do is declare whether he laughed or not. Yes, that credit does have the faint whiff of “by William Shakespeare, additional dialogue by Sam Taylor” to it, but it can’t be helped. Anything needs to be adapted if it’s going to work in another medium — which is a big “if” — and having it done by one person, who then lays out and draws the thing himself, is about as pure an auteur case as you can get.

Yes, that credit does have the faint whiff of “by William Shakespeare, additional dialogue by Sam Taylor” to it, but it can’t be helped. Anything needs to be adapted if it’s going to work in another medium — which is a big “if” — and having it done by one person, who then lays out and draws the thing himself, is about as pure an auteur case as you can get.