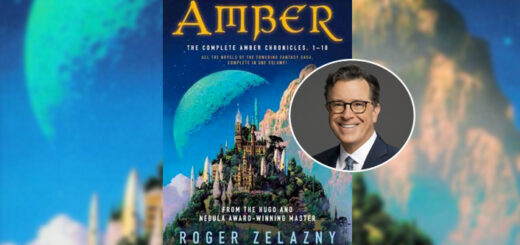

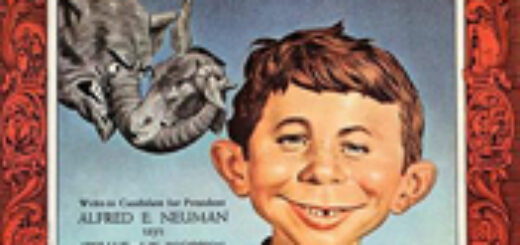

Stephen Colbert, we have your writer for “The Chronicles of Amber”!

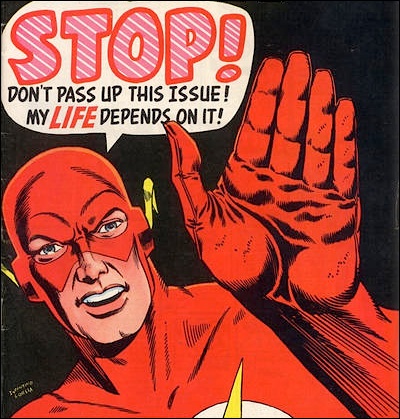

You may have seen the piece in Variety that America’s leading fanboy with a late night talk show Stephen Colbert is joining the team that is adapting Roger Zelazny’s “The Chronicles of Amber” for television as an executive producer of the potential series under his Spartina production banner, joining with Skybound Entertainment and Vincent Newman Entertainment. “The Chronicles of Amber” follows the story of Corwin, a prince who awakens on Earth with no memory who soon discovers that he is a member of a royal family that has the ability to travel through different dimensions of reality and rules over the one true world, Amber.

The Variety article also notes: “The search is currently on for a writer to tackle the adaptation.” The story of Amber is complex and requires a writer who can navigate different worlds, characters, and timelines.

Stephen, bubullah, we have just the guy for you: John Ostrander.

If you don’t know John (and for the purposes of this column, we’ll say you don’t) he’s a highly accomplished and popular writer who has made significant contributions to the world of comics and fantasy literature (as well as contributions to this website) with particular advantages that make him just the guy for this job.

First and foremost, Ostrander knows his heroic fiction. He’s written for DC, Marvel, Star Wars, and is the creator of “The Suicide Squad,” the cult classic comic that has been adapted into two feature films and a television series. The series follows a group of supervillains who are recruited by the government to carry out dangerous missions in exchange for reduced sentences. This showcases Ostrander’s ability to create compelling and complex characters, a skill that would be invaluable in adapting “The Chronicles of Amber.”

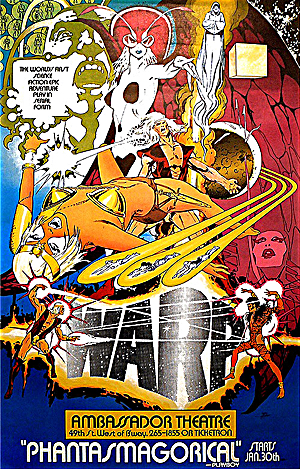

In addition to “The Suicide Squad,” Ostrander also created the character GrimJack, a hard-boiled private investigator who operates in a dystopian interdimensional crossroads. GrimJack was so beloved by Roger Zelazny that Zelazny not only wrote the introduction to the GrimJack graphic novel Demon Knight (reprinted in GrimJack Omnibus 5, ahem), Zelazny bodily lifted GrimJack and included him in the seventh book of the Chronicles of Amber, Blood of Amber, as “Old John”, an emissary of the Crown of Amber who worked for both Random and Oberon. This shows Ostrander’s ability to create a character that resonates with fantasy audiences, and Zelazny’s stamp of approval is a testament to his talent.

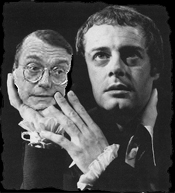

Another reason Colbert should consider hiring Ostrander is his relationship with Del Close, who also happened to be Colbert’s improv teacher and director at Second City Chicago. Ostrander and Close were writing partners, and their collaboration resulted in the graphic horror anthology Wasteland for DC Comics and several installments of the “Munden’s Bar” backup feature in GrimJack. This connection not only highlights Ostrander’s versatility as a writer but also his ability to work well with others, which is essential in a collaborative medium like television.

In conclusion, Stephen, it should be obvious that you should hire John Ostrander for the adaptation of “The Chronicles of Amber” for television. His experience in writing media-friendly high fantasy, creating complex characters, and his connections to Zelazny and your former teacher make him an ideal candidate for you. Give him a call.