John Ostrander: Talking The Talk

So you had a story idea and you’ve worked it up into a plot. The characters are defined, you know who is doing what, the twists and turns and even the theme.

So you had a story idea and you’ve worked it up into a plot. The characters are defined, you know who is doing what, the twists and turns and even the theme.

Now you have to put words into everyone’s mouths or, more precisely, into their word balloons. For some would-be writers, that’s where the wheels come off. How do you write dialogue? More importantly, how do you write good dialogue?

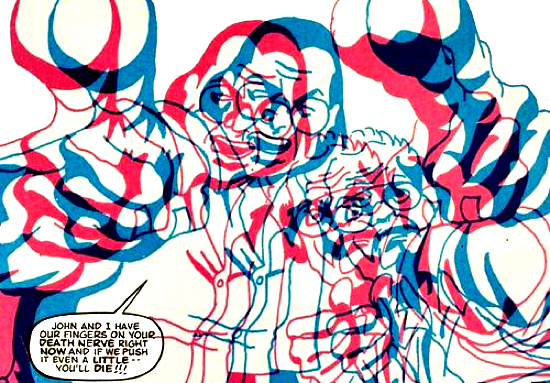

Let’s start with a basic: all dialogue is action. No one just speaks: they cajole, they explain, they confirm, they deny, they confront, they exalt, they exult, they attack, they defend, they lie and so on. It is an active transitive verb. When a character speaks, they are doing something or attempting to do something. What’s important is not what the character is saying but what the character is doing or trying to do when they speak. What does the character want, what goals are they trying to achieve? In short, what drives them? What is their motivation? What do they need? Not just want – need.

Dialogue has two main purposes: to move the plot along and/or to reveal character. Even exposition falls under the “move the plot along” rule.

Keep in mind that in comics, you have very little room for dialogue. Each panel has room for maybe two word balloons – three, if they’re small. Each word balloon has room for two to three lines tops. And you can’t do that in every panel; the reader will just see too many words and skip the page.

I’ve heard it said that comic book scripting is revealing character via newspaper headlines. So you have to be succinct with your verbiage.

Major Ostrander rule: when in doubt, cut it out. If they can (and do) cut Shakespeare, they can (and should) cut some of your lines. You should do it first. I’ve heard a story that legendary writer and editor Robert Kanigher, when he was writing Sgt. Rock, would stand on his desk and shout out the dialogue; if it sounded okay doing it that way, he figured it was right.

Once I delivered a GrimJack script to First Comics and, while editor Rick Oliver was going through it, I was schmoozing the rest of the office as I usually did. Rick came out to me with a page of script in his hand and the matching page of art. He looked at them, looked at me, and asked how much I was paid per page. I told him and then Rick noted “So on this page we’re paying you one hundred dollars for six words.”

“No,” I replied easily; “You’re paying me for knowing which words to leave off.” I offered to add more if Rick really felt it was necessary but he smiled, said he was just curious, and went back into his office.

When writing dialogue, you need to differentiate between characters. They are not all the same characters (even though all of them are you) and so should speak differently. Some people speak brusquely, some like the sound of their own voices. Some people try to over explain their reasons why they are doing what they’re doing; they feel that if you understood, really understood, you’d do things their way. I was told once by one such person that I wasn’t listening, to which I replied, “Just because I don’t agree with you doesn’t mean I’m not listening.”

There is a cadence to how people speak and that’s especially useful if you’re trying to indicate a person has a foreign accent; there is a way of speaking, a certain order. Some movies can give you a wealth of accents to hear; Casablanca is a very good one. Listen and learn.

There’s a simple short-cut that can help you; cast your characters as if they were in an animated feature. Who would you cast as their voice? The nice part of this is that it doesn’t have to be an actor; it can be anyone whose voice you can hear in your mind – a friend, a relative, a co-worker, a politician and so on. They don’t have to be currently living, either; past or present will do.

Listen to your characters as well once you have their voices in your mind; they will not only tell you what to write but may take the plot off in a direction you hadn’t considered. Listen to them and go with them if they do that. There was a GrimJack story once where I refused to do that; I stubbornly stuck to the lines and the plot that I had already decided on. That s.o.b. Gaunt stopped talking to me for the rest of the issue; it was the hardest GrimJack script I ever attempted. I learned my lesson and haven’t done it since.

Listen to people all around you; what do they say and how do they say it? What do they not say? What is left unsaid? In art, negative space can help define the figure. In writing, the silences can define the character. When do they happen, why, and what happens as a result?

Don’t be “clever.” Dialogue should be entertaining, yes; that’s part of storytelling. However, when I encounter “clever” dialogue, it means the author is really trying to draw attention to him/herself. “See how clever I am? Isn’t that a great turn of phrase?” It draws the reader right out of the story and that’s a failure to communicate. There are many writers whose dialogue is clever but that’s not their purpose. Brian Michael Bendis is an example of someone who writes very clever dialogue but he is also a very very good writer because his first focus is story and characterization. He just happens to be clever as well.

Your dialogue can be contemporaneous; it can be elevated. Poetic or streetwise. What it has to do is serve the story and reveal the character.

That’s the job.