Mike Gold: Snappy Skippy Williamson

In this space two weeks ago, I wrote about the death of cartoonist and comix legend Jay Lynch. I noted his half-century friendship with Skip Williamson; despite their physical distance, I don’t think two people could have been closer.

As fate would have it, Skip died eleven days after Jay. Each was 72 years old. For long-time friends of the pair, for long-time fans of the pair – and I count myself among both groups – the timing was crippling. Skip long had heart problems so even though it was shocking, it wasn’t totally unexpected. However, there’s a kind of appropriateness about that timing that makes complete sense.

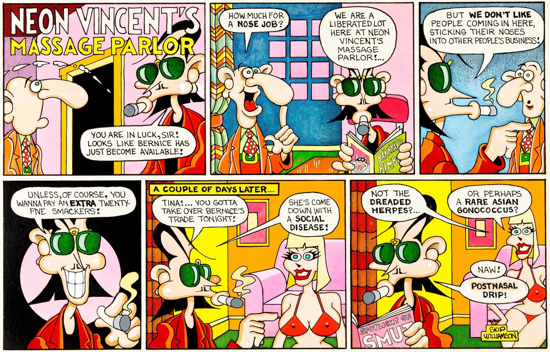

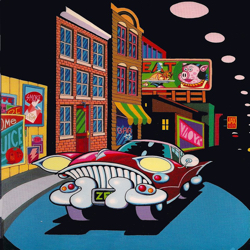

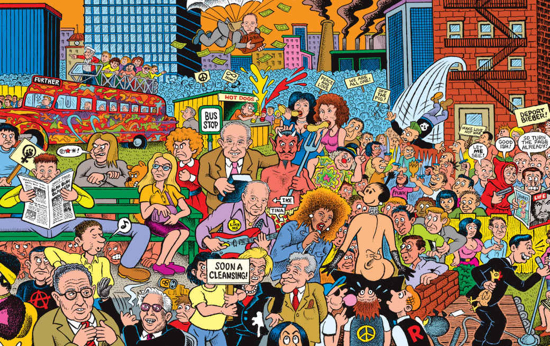

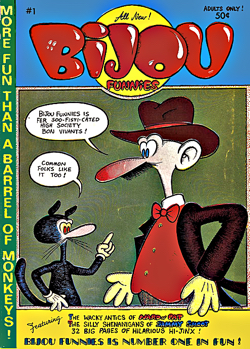

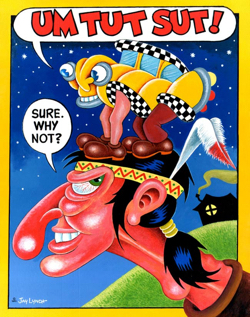

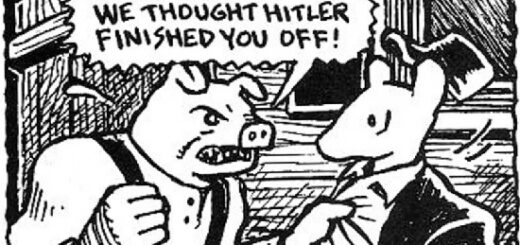

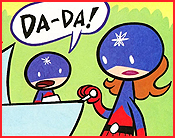

I won’t repeat their mutual history other than to mention the first comic book they pioneered was Bijou Funnies. Both had contributed to Harvey Kurtzman’s Help! Magazine and, later, to Playboy. Skip’s most revered character was Snappy Sammy Smoot, a hippie take on Ernie Kovacs’ popular character Percy Dovetonsils, only – and incredibly – even more surreal. His Neon Vincent’s Massage Parlor might have been better known as it was published monthly in Playboy, but it was Snappy Sammy Smoot who endured.

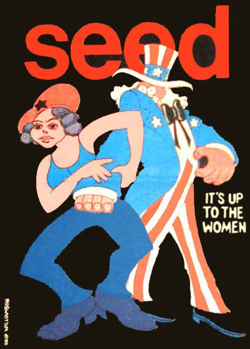

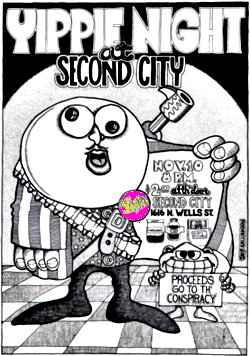

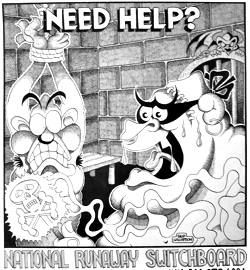

In fact, one of Smoot’s final appearances was right here at ComicMix. When we brought back John Ostrander’s fabled Munden’s Bar feature, I asked Skip if he would do our first new story. It has been reprinted in trade paperback and continues to be available here online in our comics section. Skip and I also worked together on many other projects for the Conspiracy Trial (the underground comic Conspiracy Capers was the first comic book with which I was involved; that was in late 1969 and was financed by a one thousand dollar bill I talked Abbie Hoffman into giving me), on the Chicago Seed, for the National Runaway Switchboard, and on various music and radio projects.

Skip’s contributions to Playboy paid off well: he became art director and frequent cover artist at Playboy Press, publisher of many books and paperbacks. It was through this connection that Skip introduced me to Harvey Kurtzman… at the original Chicago Playboy mansion, no less.

Skip’s contributions to Playboy paid off well: he became art director and frequent cover artist at Playboy Press, publisher of many books and paperbacks. It was through this connection that Skip introduced me to Harvey Kurtzman… at the original Chicago Playboy mansion, no less.

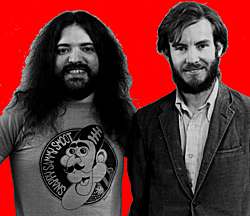

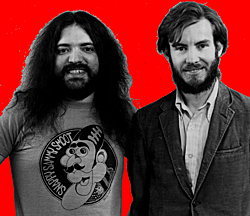

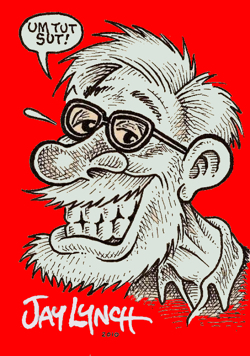

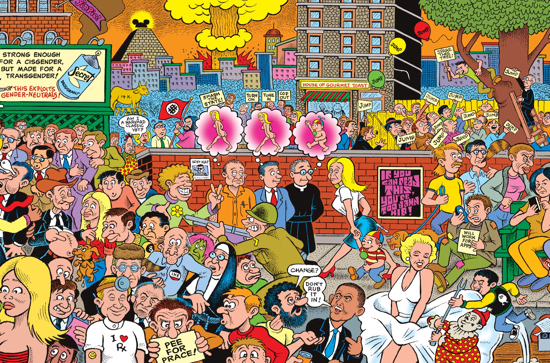

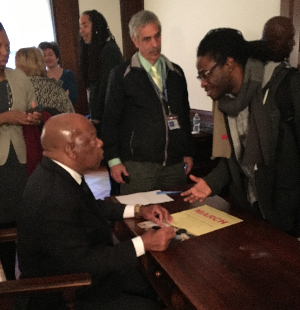

Skip maintained the radical political point of view that was typical of the late 60s and early 70s – and he kept it all his life. Physically, as you can see from the photo, Skip actually looked like he drew himself. Not in comics; in real life. Such as it is.

For a while, Skip lived in a nice apartment in Evanston Illinois, just north of the Chicago city limits. From there he would occasionally take LSD and gawk at the folks who lived in next-door Skokie, a town that was known, somewhat undeservedly, for its middle-class lameness. Amazingly, when I moved back to Illinois after my first stint at DC Comics in the late 1970s, I rented Skip’s old apartment. But I wasn’t the one who actually found the apartment, my first wife Ann scouted the place out before I got there. I walked through the flat when it was empty and got a funny vibe, as though I had been there before. I finally realized that I had, and I stayed there nearly nine years until I went back to DC Comics here in the Atlantic Northeast.

A man with a great sense of humor and a truly unique worldview, Skip was a proud father and a wonderful husband. And a swell friend.

In the realm of cartoonists, in addition to the underground crowd populated by such friends as Robert Crumb, Art Spiegelman, Gilbert Shelton, Kim Deitch, Ralph Reese and Denis Kitchen, Skippy shared the same slice of the comics pie as masters like Jack Cole, Basil Wolverton and Dick Briefer – but, somehow, moreso. Like Ernie Kovacs, Skip believed in the concept of nothing in moderation; at least in cultural terms.

It’s hard to believe Skip and Jay are no longer here. In recent years I’d see them together at various conventions; that’s how us old-timers stay in touch with the rest of the donut shop. But now we’re two stools light.

It’s hard to believe Skip and Jay are no longer here. In recent years I’d see them together at various conventions; that’s how us old-timers stay in touch with the rest of the donut shop. But now we’re two stools light.

• • • • •

O.K. I’m ending with a personal note. I might sound like I’m whining, but I’m just overwhelmed. We’ve lost a lot of great people in the past two weeks or so. Some, like Jay Lynch and Skip Williamson and Bernie Wrightson, were friends of many decades standing. Others like Dave Hunt were co-workers who I knew and liked, and still others – the unbelievably gifted Jimmy Breslin and the George Washington of American music, Chuck Berry – are people I’ve interviewed and worked with. So it’s been a bit tough here in La Casa del Oro. Michael Davis gave us his Bernie Wrightson story in this space yesterday. We’ve got to stop losing all these great talents, now when we need them the most.