John Ostrander: Belief Suspended

There’s the concept in fantastic literature known as the “willing suspension of disbelief” by which the reader/audience accepts fantastic elements in a story that are not found in reality, semi-believing them for the moment for the sake of the story. If the creator is invoking it, he or she must be careful not to jar that suspension of disbelief.

It’s an important concept for those of us who labor in the fields of SF, fantasy, horror, and comics. Two things I find crucial to make the concept work – an internal consistency within the story and a consistency within the continuity. By an internal consistency I mean that something that was given as true on page five remains true on page thirty. If the character knows something they can’t suddenly un-know it just for the convenience of the plot. Likewise, if something has been established as part of the continuity, you can’t just disregard it willy-nilly. It doesn’t mean that continuity can never change but there needs to be reasons that it changes unless you’re going to do what DC does and just throw the baby out with the bathwater and start continuity over.

Something else that confounds my suspension of disbelief is when something in the story just ignores reality. I went to Independence Day and I wasn’t expecting much, just a good mindless action film. Unfortunately, there was incident after incident of things that were just patently impossible that it threw me right out of the story. To wit: Air Force One is taking off despite explosions going on all around. In fact, one explosion almost engulfs it. It comes up the tail of the plane before the aircraft manages to speed away. Never mind that the shock waves would have torn the plane apart – it was a Cool Visual.

Take an episode of Doctor Who this past season, Robots of Sherwood. Aliens are escaping Sherwood Forest on a ship that uses gold to power its furnace. A little more gold will cause the power plant to overload and explode. With the help of the Doctor and his companion, Robin Hood shoots a golden arrow at the ship that causes the ship to go boom. Never mind that the arrow would have just hit the hull and never come near the power plant. Never mind that the weight of an arrow made of gold would cause it to fly about three feet.

It’s too bad, too; I actually really enjoyed the episode up until then.

I’m willing to suspend my disbelief; after all, I was raised Roman Catholic and you’re told by the Church to believe that a wafer of bread becomes the actual body and blood of Jesus Christ and that you are supposed to eat it. As a kid, I just accepted that. I’m open to all kinds of things.

Every time I open a book or enter a movie theater or turn on the TV, I’m willing to accept the premise as possible at least for the duration of the experience. It’s when I’m not allowed to stay in that moment because I’m jarred out of it by something stupid that violates the premises listed above that I actually get a bit pissy about it. My time has been wasted and I do not take that kindly.

My own rule of thumb is to always ground the fantasy in as much reality as I can. The more accurate and real the non-fantasy parts of the story feel, the more the reader can identify with it and the more likely it is that they will accept the fantasy elements. Earn a reader’s trust and they will follow you anywhere. I know I do.

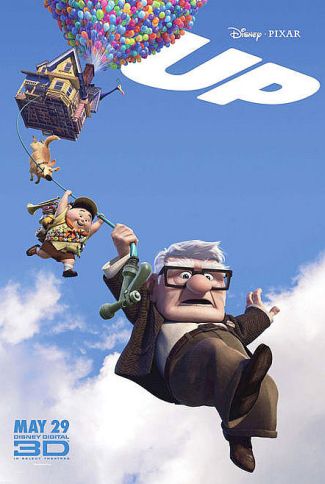

One of the things that I love about Pixar is that they

One of the things that I love about Pixar is that they John McCain, in what is assumed to be an attempt to woo feminist Hillary Clinton supporters, nominated an inexperienced first-term governor of Alaska as his running mate. In state-wide office less than two years, Sarah Palin includes in her resume a term as mayor of a small town, and a stint on her local PTA.

John McCain, in what is assumed to be an attempt to woo feminist Hillary Clinton supporters, nominated an inexperienced first-term governor of Alaska as his running mate. In state-wide office less than two years, Sarah Palin includes in her resume a term as mayor of a small town, and a stint on her local PTA.