Review: The “March” Trilogy by John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, & Nate Powell

I recently finished reading Book Three of March, the graphic novel autobiography of Atlanta Congressman and civil rights leader John Lewis. I had never heard of Lewis prior to encountering March, but having now read it, I’ve gained a better picture of not only his life, but of the internal and external obstacles that the Civil Rights movement navigated in the 50s and 60s. Living today at a time when white supremacists have actually managed to gain an inexplicable foothold back into the mainstream—something I never thought I’d ever experience in my lifetime—reading March, isn’t just a gratifying reading experience. It’s a reminder of where our country has been, and the direction from which that pendulum has swung. As we reel from the horrors of Charlottesville, religious travel bans, mass child abuse inflicted upon brown children, and the continued practices of voter suppression, March serves as a warning of what it may look like if it swings back too far.

I recently finished reading Book Three of March, the graphic novel autobiography of Atlanta Congressman and civil rights leader John Lewis. I had never heard of Lewis prior to encountering March, but having now read it, I’ve gained a better picture of not only his life, but of the internal and external obstacles that the Civil Rights movement navigated in the 50s and 60s. Living today at a time when white supremacists have actually managed to gain an inexplicable foothold back into the mainstream—something I never thought I’d ever experience in my lifetime—reading March, isn’t just a gratifying reading experience. It’s a reminder of where our country has been, and the direction from which that pendulum has swung. As we reel from the horrors of Charlottesville, religious travel bans, mass child abuse inflicted upon brown children, and the continued practices of voter suppression, March serves as a warning of what it may look like if it swings back too far.

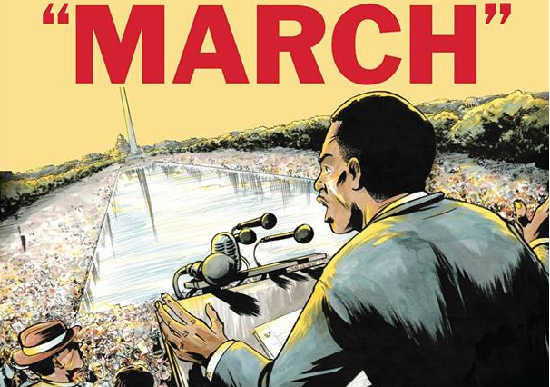

Lewis played many key roles in the civil rights movement, and the end of legalized racial segregation in the United States. As chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), he was one of the original 13 Freedom Riders, and one of the “Big Six” leaders of groups who organized the 1963 March on Washington. He was the fourth person to speak at the March (Dr. King was tenth). Only 23 at the time of his speech, he was the youngest of the speakers, and is the only one still living.

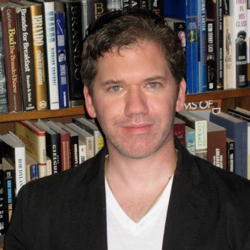

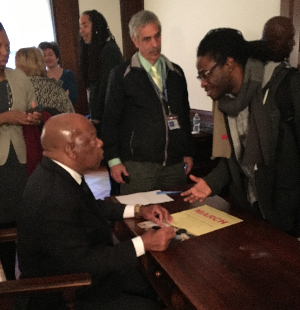

The author’s photo of the creative team, from left to right: Nate Powell, Andrew Aydin, and Congressman John Lewis.

I first became acquainted with March in 2013, when Book One was published by Top Shelf Comics, and I covered the signing held at Midtown Comics in Manhattan as a photographer for Wikipedia. Congressman Lewis was in attendance, along with his Digital Director and Policy Advisor Andrew Aydin, who conceived the idea for the book and co-wrote it with him, and artist Nate Powell, who illustrated and lettered the book. Book Two followed in 2015, and Book Three in 2016.

While March obviously isn’t the first work dealing with the history of the civil rights movement, and is not the first autobiography Lewis has written (his prose memoir, Walking with the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement, was published in 1998), March is unique in that it is a graphic novel, a medium chosen for its ties to the history of the movement, and to Lewis’ role in it. Lewis first heard of Rosa Parks, Dr. King and the Montgomery Bus Boycott through his mentor, James Lawson, who worked for the Fellowship of Reconciliation (F.O.R.), an interfaith organization dedicated to promoting peace and justice. Lawson gave Lewis a copy of Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story, a 10-cent comic book published by F.O.R. that demonstrated in clear fashion the power of nonviolence. The Montgomery Story served as one of the guides used at student meetings that Lewis began attending, and influenced other civil rights activists, including the Greensboro Four. Aydin repeatedly suggested to Lewis that he write a comic book of his own, bringing him back full circle to the medium that got him involved in the movement.

While March obviously isn’t the first work dealing with the history of the civil rights movement, and is not the first autobiography Lewis has written (his prose memoir, Walking with the Wind: A Memoir of the Movement, was published in 1998), March is unique in that it is a graphic novel, a medium chosen for its ties to the history of the movement, and to Lewis’ role in it. Lewis first heard of Rosa Parks, Dr. King and the Montgomery Bus Boycott through his mentor, James Lawson, who worked for the Fellowship of Reconciliation (F.O.R.), an interfaith organization dedicated to promoting peace and justice. Lawson gave Lewis a copy of Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story, a 10-cent comic book published by F.O.R. that demonstrated in clear fashion the power of nonviolence. The Montgomery Story served as one of the guides used at student meetings that Lewis began attending, and influenced other civil rights activists, including the Greensboro Four. Aydin repeatedly suggested to Lewis that he write a comic book of his own, bringing him back full circle to the medium that got him involved in the movement.

And what a story it is.

The story opens in media res on March 7, 1965, as the young Lewis stands on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama with fellow civil rights activists during the Selma to Montgomery marches, which serves as a framing sequence that bookends the trilogy. The activists are confronted by Alabama state troopers, who order the protestors to turn around. When the protestors kneel to pray, the troopers attack them, before the narrative cuts away to Lewis’ beginnings.

Lewis grew up on his sharecropper father’s farm in rural Alabama, tending to the family’s chickens while entertaining dreams of becoming a preacher. Eventually, his eyes were opened to the state of race relations in the United States by his school studies, and by his maternal uncle Otis, who took Lewis on his first trip up North in June 1951. Lewis describes the careful planning that had to be made for such trips in order to avoid places where black people were not wanted, and the caution Otis observed as they drove through Alabama, Tennessee and Kentucky. Their relief comes only when they make it to Ohio, which is accompanied by the image of their car driving across another bridge, a fitting recurring motif.

Although his parents had raised him to stay out of trouble, the experience of seeing whites and blacks living side and by side in the unsegregated North changed Lewis so much that home never felt the same to him. When he started school again, the segregated bus he rode to school was a daily reminder of what he had learned about the two worlds that existed in the United States. When Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka outlawed public school segregation, Lewis thought it would improve his schooling, but his parents continued to warn him, “Don’t get in trouble. Don’t you get in the way.” Lewis also noticed that the injustices against blacks were not mentioned by local church ministers, and that his minister drove a very nice automobile. Profoundly inspired by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s social gospel and the Civil Rights movement that he heard in a Sunday sermon by King on the radio, Lewis preached his first public sermon just before his sixteenth birthday, garnering his first publicity. While attending American Baptist Theological Seminary Lewis sought to transfer student to Troy University, and when he was rejected because he was black, it led to his first meetings with civil rights leaders Ralph Abernathy and Fred Gray, and then Dr. King. Lewis was told they would have to sue the state of Alabama to change this, but since Lewis was still a minor, he would have to get his parents permission for this. Lewis was heartbroken when his parents refused, but he would continue his work in Nashville, where his moral philosophy on racism, poverty and war was shaped by other activists there like Diane Nash and Jim Lawson, and those far away like Mohandas Gandhi. From here, Book One of the trilogy depicts Lewis and the Nashville Student Movement’s lunch counter sit-ins, and the tactics they learned to employ in response to racists who inflicted abuse and beatings upon them, and how they dealt with arrests.

Book Two depicts the expansion of the Nashville student movement’s respectful protests, Lewis’ involvement with the SNCC, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), and the Freedom Riders; their confrontations with opponents like Bull Conner and George Wallace; and the resulting beatings, shootings, firebombed buses and imprisonment. Their activities caught the attention of the initially equivocal Attorney General Robert Kennedy, and that of others who decided to become Freedom Riders themselves—swelling the movement’s numbers so that even imprisonment wouldn’t be a feasible way for the white establishment to stop them. As Lewis put it, “The fare was paid in blood, but the Freedom Rides stirred the national consciousness and awoke the hearts and minds of a generation.” The SNCC also faced a schism between those who favor their effective direct action campaigns and those who favored Dr. King and Robert Kennedy’s urging to focus on registering blacks to vote. When Jim Bevel and the South Christian Leadership Conference organized Birmingham’s black children to protest, a thousand children were arrested, and the televised images of fire hoses and German shepherds being used against kids horrified the nation. As Lewis is elected chairman of the SNCC, he is moved by the surreal nature of being invited for a meeting with President John Kennedy and other black leaders at the White House, where the March on Washington is first announced.

Book Three opens with the September 15, 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham. The SNCC continues its work amid the assassination of JFK; and continued violent resistance to the Civil Rights movement, which includes the murder of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner. President Lyndon Johnson signs the 1964 Civil Rights Act, but it does not ban “literacy tests” and other voting restrictions. What remains to be achieved is a voting rights bill, but Johnson’s need to court Southern voters in the upcoming election spurs him and his supporters to put pressure on civil rights activists to stop the protests. This gives cause for conflict between Roy Wilkins, who favors ceasing the protests, King, who suggests a moratorium on them, and those like Lewis and James Farmer, who are adamant that protests must continue. The murder of activists like James Reeb and 26-year-old Army veteran Jimmie Lee Jackson seem to threaten to shatter Lewis, but also seem to steel his resolve for the Selma to Montgomery marches, which brings him to the Edmund Pettus bridge, and back to the scene that opened the trilogy. Chaos breaks out as state troopers brutally beat and tear gas activists, which becomes known as “Bloody Sunday.” Lewis’s skull is fractured, but amazingly, he escapes across the bridge to safety, and appears on television to call for Johnson to intervene before he even goes to the hospital, bearing scars from that beating to this day. The photo of the unconscious Amelia Boynton Robinson, pummeled nearly to death, so shocks the world that it raises the public’s consciousness on the need for lawmakers to act. It’s probably not for nothing that the crowd crossing the Edmund Pettus bridge is the cover image of the slipcased three-book set, beautifully silhouetted against the Sun.

What I appreciate about this story is the genuineness of the conflict among not just racists and civil rights activists but among the various individuals and groups of the movement. While multiple layers of conflict is part of writing fiction, this is often not possible when telling a non-fictional story authentically, and can result in writers either fabricating events and conflicts that never happened, or telling a story in a way that seems flat and boring. Neither occurs in March. Preparations for the March on Washington, for example, which one may think, with the auspiciousness granted to that event by the hindsight of history, was brought about by winds of inevitability, was anything but. Behind the scenes, arrangements are marked by tension over passages in Lewis’s speech that are seen as anti-Catholic, and possibly pro-Communist. This is a clash that I never knew took place prior to the reading this book, and its inclusion makes the read both entertaining and educational.

I also appreciate that Lewis does not make the movement about him, and gives space to discussing figures I had previously heard little or nothing of, like Bob Moses, Stokely Carmichael, A. Philip Randolph, and Bayard Rustin. While evaluating a work of non-fiction is more difficult than a work of fiction, in part because one can’t be certain how much is accurate, the fact that Lewis explains who everyone else is goes a long way to conveying a feeling of authenticity, and the sense that I’m learning much I never learned in high school, or even during the boilerplate television programming we get every February. Lewis doesn’t skimp on the emotional moments either, and there are plenty in this book. Particularly powerful is a moment when Robert Kennedy cements Lewis’s respect for him when he pulls the young activist aside and says to him, “You, the young people of SNCC, have educated me. You have changed me. Now I understand.”

Nate Powell’s art is perfectly suited to this type of book. Using a combination of ink and ink wash, with an adeptly varied line weight, the greyscale art does a good job of evoking a sense of time and place. Powell knows when to apply his technique judiciously, making competent use of shadows, silhouettes and high-contrast black and white compositions during dramatic moments, and even rendering some panels in a light, all-pencil technique.

The power of Powell’s depiction of historical figures lies not in fealty to standards of photorealism, but from his ability to elicit feelings with his visuals: Characters set against completely black background, their figures rendered in the sparse areas illuminated by a lone light source, convey a feeling of their isolation, while a farmhouse drawn in one or two light tones of grey against an all white background transport the reader to the sun-drenched fields of the rural South. While I like color, even prefer it, one never feels cheated when looking at the art in this book.

Praise also needs to given to Powell’s excellent depiction of each character’s features. In an industry where artists often have one or two stock “faces” that they use on every character, to illustrate 445 pages of a story featuring dozens of real-life people, many of which have to be distinguishable to the reader page by page, is a considerable undertaking. Powell wisely chose not to go the photorealistic route by constantly referring to photos, which for some artists, can result in stiff, lifeless characters. Instead, he developed a visual shorthand “master drawing” for each character, one that emphasized their skull structure, to serve as a reference for their features. One need only look as far as any number of licensed comics, like some of the Star Trek books, which look like they’re drawn by artists who simply copy publicity photos, to see how well Powell avoided this problem. His characters are historically accurate yet vibrant and fluid.

The only criticisms I have is that in some instances, Powell’s designs deviate a bit too far from the person’s actual likeness, as with the portraits of FDR, JFK and Truman hanging above the stage at the 1964 Democratic convention, which look nothing like those men, and would not have been recognized out of context, or without the labels that Powell placed above each portrait (which were not at the actual convention). Kennedy seems to be a particular problem for Powell in other places in the trilogy. This required me to go back and re-read dialogue to verify who he was, and when that happens in a comic featuring one of the most beloved figures of the 20th century, it’s time to go back to the drawing board. Powell also seems to have the same problem that some other artists have when rendering the human face at an angle, apparently not having mastered how the eye and eye socket looks in three-quarter view, or in perspective. There’s also that bizarre line Powell uses on Page 126 of Book Three to connect the ground seen in Panel 2 with the top of Lewis’ head in Panel 3. Nonetheless, these issues are few and far between, and overall, the book is a triumph for Powell.

Since comics are a visual medium, I should also talk about how the visuals are nicely balanced with the text. This book is an autobiography dealing with the various political and cultural conflicts of the civil rights movement, and by necessity, entails much discussion among characters. This can be tricky for comics, and for that matter, any visual medium, including film, television, etc.. Do it right, and you have masterpieces like Sidney Lumet’s enthralling 1957 feature film adaptation of Twelve Angry Men, easily my favorite black and white film, which set almost entirely in a small jury room and driven entirely by dialogue. Do it poorly, and you get the last couple of historical dramas by Steven Spielberg, which I found flat and sleep-inducing. March, however, gets it right. Rather than publish a smaller book by omitting important details that explain what the challenges that Lewis and his colleagues faced, the book’s size allows space to be given to the important discussions and arguments that occurred among different groups in the movement, and does so in a way that does not come across as overly heavy with word balloons. Lewis, Aydin and Powell manage to do this in a way that the story and dialogue is seamlessly incorporated with the art, so that the amount of space given to each scene feels appropriate. Six pages are devoted, for example, to Lewis’ speech at the March on Washington, and as a result, it both reads well and looks good.

The fact that Powell lettered the book too may also help explain its narrative success, and one gets a sense of how closely the three creators worked together to effect what seems like a genuine shared vision rather than an assembly line product. While lettering isn’t something I often notice, it’s an unsung hero of comics, and Powell’s unique approach to it, incorporating it into the book’s landscape stands out. A Bible verse being read by the prepubescent John sitting in silhouette on his porch is written out in the black area of his back, conveying out the words penetrated his very soul. An important announcement heard on a radio aren’t depicted so much as the typical floating clouds rendered above the device as it is jagged billows of electricity spit out by the radio, as if it is as much a character as those listening to it.

I can’t stress enough what an important work this is. If you love to read, buy it. If you want to expand your comics reading list with more non-superhero works, buy it. And if the re-emergence of David Duke and the murder of Heather Heyer horrify you, then buy several copies and give some to your friends.

And above all, VOTE.

Better than men than you and I have had their skulls cracked open for that right.