Science Friction, by Dennis O’Neil

The following will be about a column I didn’t write and it’s Vinnie Bartilucci’s fault. But that’s okay. I forgive him.

The following will be about a column I didn’t write and it’s Vinnie Bartilucci’s fault. But that’s okay. I forgive him.

What Mr. Batilucci did was beat me to recommending Physics of the Impossible, by Michio Kaku. This Mr. B. did in a comment on last week’s column which, some may remember, described how awkward I felt being a published science fiction writer who was abysmally ignorant of science and how one of my earliest attempts at remedy of this ignorance was reading One…Two…Three…Infinity, by George Gamow.

My plan was to save recommending Dr. Kaku’s much more recent book – it’s on current best-seller lists, in fact – for this week.

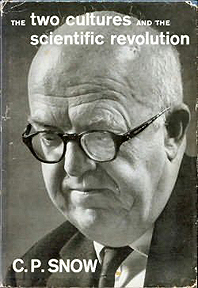

Said recommendation would have come at the end of a blather that would have mentioned yet another elderly book, The Two Cultures, by a remarkable man who was both a scientist and novelist named C.P. Snow. According to the endlessly useful Wikipedia, “its thesis was that the breakdown of communication between the “two cultures” of modern society – the sciences and the humanities – was a major hindrance to solving the world’s problems.” I encountered Mr. Snow’s slim volume in college, probably when I should have been reading something some teacher had assigned, and it must have impressed me. (I mean, here we are, all these years later, and I still remember it.) The unwritten column would have culminated in the reiteration of something I mentioned some months ago, advice from my first comic book boss, Stan Lee. Stan said, in effect, that it’s a waste of space to “explain” comic book “science” because readers will accept what we tell them.

I might have added, if I’d written this week’s column, that even if we know the science, it might be difficult to insert it into an entertainment without wreaking havoc on drama and structure and pacing and all that Fiction Writing 101 stuff.

Again, I would have suggested, had Mr. Bartilucci not stolen my thunder, that we should not pervert real science. As I wrote in that earlier piece, “readers who know and respect the reality will be yanked out of your fictional world if you get it wrong and insult their intelligence, perhaps never to return, and you don’t want to abet the alarming ignorance about science that seems to prevail in our nation… made-up technology is fair game, made-up basic facts aren’t.”

Once, a long time ago, I edited a story by a writer I know to be smart and talented in which galaxies seem to be confused with solar systems. A fifth grade mistake – or, at least, it should be a fifth grader. But given the dismal performance of our young scientists and mathematicians, maybe my writer’s error was normal. (In a recent survey of 30 countries by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, U.S. kids placed twenty-first in science and twenty-fifth in math. Sad, huh?)

I might have concluded the never-to-be-perpetrated column with the proposition that writers, even writers of fantasy melodrama, shouldn’t augment the world’s ignorance.

I guess we’ll never know.

RECOMMENDED READING: Well, since this week’s column didn’t get written, I can’t recommend anything. But any books whose titles you may have come across in…oh, say, the last ten minutes might be worth your time.

Dennis O’Neil is an award-winning editor and writer of Batman, The Question, Iron Man, Green Lantern, Green Arrow, and The Shadow – among many others – as well as many novels, stories and articles. The Question: Poisoned Ground, reprinting the second six issues of his classic series with artists Denys Cowan and Rick Magyar, is on sale right now, and his novelization of The Dark Knight will be available in a couple weeks or so.

There has to be a balance between the smack-your-forehead pseudo-science in some comics and the overly pontificated theories in others (I'm looking at you, Warren Ellis).Another good book on science (hope I'm not stealing next week's column!) is The Structure of Scientific Revolution, which traces the history of scientific progress and shows that it hasn't been as clean of a development as we believe.

One of the more interesting conferences I've attended in my professional life was in Northern Ireland, sponsored by the ARDS Council, that paired scientists and creative artists. I was invited as a writer ( a long and separate story but thank you, Jim Murdoch). The theme was how art influences science and vice versa. I was the opening speaker. GAH! All the scientists were there as well. GAAAAH!!! I THINK I managed not to sound like a complete idiot. As I recall, my theme was how the arts can fire the imagination and inspire scientists, sometimes even to BECOME scientists. Some astronauts credit STAR TREK with their desire to go into space, for example.For me, part of the problem when we just "make up the science" is that we do the same with human behavior. All fantasy needs to have one foot firmly set in reality if its going to reflect our human lives at all (and it needs to do so). In fact, I think you taught me that when you were my editor, Denny.

"Some astronauts credit STAR TREK with their desire to go into space, for example." Yep. And the first generation of NASA people credited Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon. I gotta tell you, the most inspirational stuff I've seen in years are those pictures from Mars. I still sit there amazed and awestruck. And that's the true value of the space program. That, and Tang.When it comes to "making up the science," I recall the words of my former office-mate (and yes, I was damn lucky here). He said "Well, it might be phony science, but it's OUR phony science." In other words, create your own rules and then stick to them.Oh, yeah. The guy who uttered that axiom? Dennis O'Neil.

Quote: "Well, it might be phony science, but it's OUR phony science." In other words, create your own rules and then stick to them.I think that advice summarises the best way to deal with "phoney" or pseudo-science. Okay, so you're dealing with stuff that doesn't agree with the current scientific paradigm, but provided it follows a set of reasonable rules, suspension of disbelief can be maintained and the story enjoyed on its own merits with the PSB as (hopefully entertaining) colour in the background. The important thing is to keep it consistent: don't have your hero able to fly through the sun one issue/week and then have him taken out by a guy with a flame-thrower the next — not unless that's one heck of an uber-powered flamer, and is specified to be so, so that the audience can appreciate that the hero is in deep kimchee when facing it.It's when the "rules" — powers, laws of PSB physics/magic/whatever, etc. — are inconsistent, so that it's never really certain what will happen next — and not from a dramatic stand-point, but from a point of expectation of how the fictional universe works — that the whole thing breaks down and it becomes tedious. The only person who can reasonably get away with such big changes is John Ostrander when writing GrimJack, because he's already specified that the laws of reality can change when someone crosses the street, and that has been used to good comic effect by both John and other authors when playing in Cynosure. Everyone else needs to choose a set of rules and stick with them; they may not be the laws of science as we know them, but provided they're consistent, they can be used to make the story work.

Um…oops? Remind me not to discuss your triumphant return to writing Batman, so there'll be no excuse for you to skip it…I've always been a proponent of comic book (or science fiction) science. After all, once you accept the concept of the man from another planet who can fly and use heat vision, arguing the physical feasibility of how the heat vision works is a little disingenuous. It does; move on. But my pet peeve is that once a writer chooses to mention actual, proper science, he should get it right. Much like my standard overreaction for the misuse of "it's" and "its", when I see a writer use "Light year" as a measurement of time, I get jolted right of the story like Christopher Reeve seeing the shiny penny. Now, I was willing to accept that Long, Long Ago In A Galaxy Far Far Away, the "Parsec" could be a unit of time, so the Kessel Run could be done in under twelve of them, but if it's in this universe, getting stuff like that wrong just…rankles.Kurt Vonnegut once wrote an essay (Creatively titled "Science Fiction", collected in _Wampeters, Foma and Granfalloons_) in which he bemoaned the fact that he was often pigeonholed as a science fiction writer BECAUSE he knew a little about science. His complaint was that just because you understand how a refrigerator works, critics and the people who do such classifications assume you must be a science fiction writer. He blamed the colleges for encouraging English majors to eschew the physical sciences in favor of the freedom of pure thought.