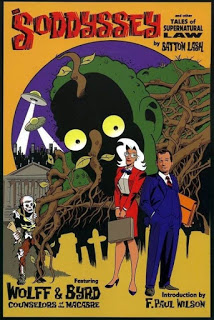

Book-A-Day 2018 #76: The Soddyssey and The Werewolf of New York by Batton Lash

I’m not a lawyer. But I’m a lot more familiar with lawyers these days, having spent the last three years working with a bunch of them (including more “recovering lawyers” than one would expect) and marketing things to lawyers all day every day. So maybe this time I came back to Batton Lash’s long-running “Supernatural Law” comics series with just a bit more understanding of who he’s talking about and what some of the jokes mean.

(The supernatural side of Supernatural Law is much simpler: Lash’s bedrock sense of the supernatural is pretty much that of monster movies from the B&W era, all Draculas, Frankensteins, and Wolfmen. There are no hot-to-trot young women with lower-back tattoos and complicated love lives, no modern wizards, no elves hidden in plain sight, no unexpected Grail quests. Actually, given that Lash isn’t a lawyer himself, his take on both sides of the equation come from similar places: general cultural knowledge. It’s just that lawyers are more common in everyday life and more apt to have complained to Lash about perceived slights.)

I read Supernatural Law back when it ran in CBG as Wolff & Byrd, Counselors of the Macabre — yes, I am old — and I think I used to read it in floppy-comics form through the ’90s and early ’00s, too. (I gave up on floppies about a decade ago, and lost twenty-five years of accumulated comics in my 2011 flood, so I can’t check.) But, like everything else in comics, Lash has been moving his creations into book and webcomic form, since that’s where the readers are these days. (Some of the comics used to be available at supernaturallaw.com , but there’s just a single “cover” image there now.)

There were two Supernatural Law collections sitting on my shelf, for longer than they should have been: The Soddyssey and Other Tales of Supernatural Law and The Werewolf of New York . Since I’m doing Book-A-Day this year, I’m running through books more quickly and actually clearing out those shelves. (Stop me before I turn into an infomercial.)

Soddyssey collected issues 9-16 of the comics series — which I think I vaguely recognized from reading in the ’90s — while Werewolf was a brand-new graphic novel created for book publication and funded by a Kickstarter campaign a few years back. But they’re both the same kind of thing: stories about supernatural creatures in legal trouble, told mildly tongue-in-cheek but with realistic legal outcomes. Soddyssey has several stories; Werewolf one. But Lash was telling a soap-opera-style story to begin with, full of life and romantic complications for his series heroes and their supporting cast, and that continues throughout, even as one case ends and another starts.

Alanna Wolf and Jeff Byrd are the principals of a small law firm, one that concentrates not on a particular area of law — though they do end up involved in litigation more often that not, since that spells “law” to a non-legal audience — but on a particular kind of client. One might wonder how all of these diverse creatures know to make their way to Wolff & Byrd, or how likely it is that they all have legal troubles in a state where those two are barred, but that’s the premise. We’ll be here all day if we start to question premises.

Supernatural Law always felt old-fashioned to me, in the best way, as if it should have been a daily-comics strip like The Heart of Juliet Jones or Mary Worth — something more culturally central than it really was. These two collections give me that same sense: Wolff & Byrd do the kind of law you’d see on TV fifty years ago. They’re not brokering the merger of the Seelie and Unseelie Courts, or negotiating the transfer of IP from a banshee to a hot new pop star, or handling the import paperwork on a half-ton of grave dirt. They’re filing briefs, traipsing back and forth to court to plead in front of a judge, and counseling their current client to keep his mouth shut. (Always good advice, from any lawyer to any client.) It’s the kind of law you recognize, even if you don’t know anything about law.

These are fun stories about that kind of law, with some inventive twists on the kind of supernatural creatures you know the same way. Creator Batton Lash has been doing this, off and on, for forty years, and he makes it all smoothly entertaining.

![]()

![]()

Reposted from The Antick Musings of G.B.H. Hornswoggler, Gent.