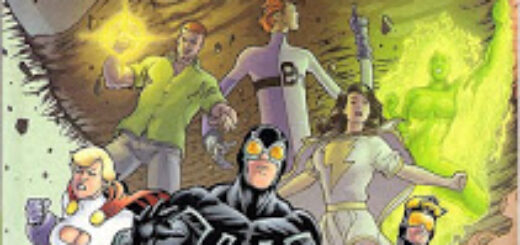

Book-A-Day 2018 #245: I Can’t Believe It’s Not the Justice League by Giffen, DeMatteis, Maguire & Rubinstein

I don’t know why the story reprinted in I Can’t Believe It’s Not the Justice League so obviously positioned itself as a one-time one-off. As a former editor and current marketer, I’m strongly against interrupting customers while they’re buying your stuff, but I’m not DC Comics.

And this book does make it clear, in little ways all the way along, that this will be just as much of this silliness as we’re going to get, so you’d better enjoy it now while you have it. (“Now” being 2005, in this case: and it’s true, we haven’t gotten any more, in the more than a decade since then.)

Maybe that was because writers Keith Giffen and J.M DeMatteis realized the high bwah-ha-ha style was harder and more demanding than they remembered, and wanted to get back to simpler punch-fests. Maybe this was all the time for penciller Kevin Maguire that they would ever get again, and they wouldn’t dream of doing it without him. (I think inker Joe Rubinstein was game for more of this, but maybe not?)

But, still: generally, during a story, you don’t look askance at your readers and mutter things like “are you actually reading that?” under your breath. Unless you’re DC Comics, obviously.

If that kind of thing annoys you, you probably don’t want to read I Can’t Believe It’s Not the Justice League. Other things might trigger that reaction: superheroes who crack jokes, running gags, repeated extreme facial expressions, sitcom-level character comedy, naivety and assholishness equally played for laughs, and lots of dialogue. (You can’t have character-based comedy without letting your characters talk.)

(I looked at the prior retro JLI story a few weeks ago.)

This follows immediately on the heels of the prior story: the Super Buddies still haven’t had a first case, but are caught up in dram with their new neighbor, a bar being run by a former (very minor) supervillain…and his partner, who turns out to be everyone’s least favorite Green Lantern, Guy Gardner. (I think at this point he had some other kind of power ring, but the story doesn’t explain — he has a ring, he can do stuff, that’s good enough.) He and Power Girl — the superhero with the famous “boob window” — are our new characters here, replacing Captain Atom, who is quietly recuperating from the events of the prior story and will not return.

The plot, such as it is, sees the Super Buddies first go to hell, and then to the usual alternate world populated by evil versions of themselves. (Is that Earth-3? I can never remember. This is probably pre-Flashpoint, so I don’t think there even was an Earth-3 in those days.)

They run around, complain, yell at each other, make jokes, and occasionally do something heroic when they’ve exhausted all other options. It’s gloriously fun and silly in an over-the-top way, in the way that superhero comics are rarely allowed to be. (The silly comics of this decade tend to be much smaller scale, for whatever reason.) Maguire is still one of the very best artists at depicting facial expressions, and he has a lot of scope here — these folks are making all kinds of faces all the way through. He has a funny script to work with, of course, which definitely helps: these are broad characters, pushed to be silly, and Giffen/DeMatteis have long experience making them funny.

You might prefer your big superheroes to be serious: it happens. If so, this is not a comic for you. You can pick, oh I don’t know, literally anything else featuring any of these characters.

![]()

![]()

Reposted from The Antick Musings of G.B.H. Hornswoggler, Gent.