National Graphic Novel Writing Month Day 3: Plot First vs. Full Script

Day 3 of #NaGraNoWriMo. Now that you’ve decided the format your graphic novel is going to take, you have to decide how you’re going to write it. For that, we have to discuss the two major schools of comics writing: Plot First vs. Full Script.

Plot First is occasionally known as “Marvel method” because Stan Lee used it a lot when he was creating the Marvel Universe and writing eight books a month in the 60s— he would pitch a plot to artists like Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, Don Heck, etc., discuss it with them and maybe type up a quick page or two for notes. Then the artist would pencil the story, after which Stan would script the captions and dialogue to fit the art. The advantage for the writer is knowing what the art looks like, and how much room there is for text, when scripting. The disadvantage(?) is that the writer loses control over pacing and composition of the art, and may get surprised when the art comes back and there’s this silvery surfer in the middle of the story, or some other addition or omission. We don’t recommend this method at all unless you have an existing relationship with the artist and editor and trust them.

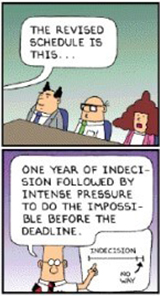

It can also lead to a sort of laziness on behalf of the writer: Frank Miller’s recent one line in a plot that John Romita Jr. turned into TEN PAGES of artwork.

Full Script: writing a complete script with panel descriptions, based on which the artist then draws the story. Advantages: the writer has more control over layout and pacing, although an artist will still find ways to misinterpret your script. Disadvantages: it takes longer to write (and may not save the artist any time), and you may need to tweak your dialogue and captions to fit the art anyway.

Because we don’t want to slough too much of the writing onto the artist for our purposes, we’re going to discuss Full Script. There’s one other method, but we’re going to save that for a bit later in our discussion, because we’re going to use elements of it in writing our script.

So what does a full script for comics look like? Well, it can look very deceptively like something it should never be… which we’ll discuss tomorrow.