To: Universal Pictures Home Entertainment; Re: “The Grinch™”

To: Universal Pictures Home Entertainment

Re: “The Grinch”

Dear U.P.H.E., we got your press release...

Afraid we can’t run it, thanks to legalese.

For as much as we might want to promote “The Grinch™”

The Seuss folks won’t budge here, not even an inch.

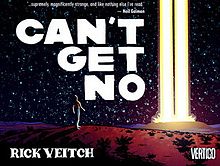

See, Dr. Seuss™ sent us a cease and desist

An action which, you understand, has us… peeved.

They told us, “Use any Seuss IP? No more!”

Not just Seuss/Star Trek mashups; Grinch™ hype too! Then... war.

They proceeded to sue us, making wild claims

of willful infringement, a charge that defames.

We're not sure that we’d want to, in any case,

assist making money they'll shove in our face

as they continue to file legal motions

and otherwise show very hostile emotions.

Our defense costs us thousands, and now you beseech:

“Please use your platform, extend Seuss's reach!

Help them make more moolah, which they’ll utilize

to stifle your speech so you can’t criticize!

Push their retelling! Please help us to coax!"

Their chutzpah is stunning. The nerve of these folks.

We don’t hold it against you, we know that it’s rough—

pushing “Grinch™” weeks after Christmas is tough.

We’d normally help; after all, ’tis the season

but we obviously can’t and now you know our reason.

If you’ve just heard about this suit, and if you think

that you’d like to contribute, please do! Here’s the link.

We’re now in the summary judgement last stages,

the judge has the filings with which she engages.

Our request for judgment should stand on its own,

the facts are all in, there’s no need to postpone.

Our motion is clear for the trained legal reader

although we admit that it’s not done in meter.

We think our case strong, we trust the judge concurs,

and fervently hope that our win she confers.

And to everyone following our long fair use fight:

Thanks for all your support... and to all a good night.