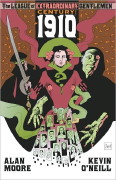

Review: The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Century: 1910

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Vol. III: Century #1

: “1910”

By Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill

Top Shelf, April 2009, $7.95

The usual rule in comics is that nothing with two or more colons in its title – not to mention two or more separate numbering schemes – is nothing but rubbishy hackwork, and should be avoided. In this, as in so much else, Alan Moore is the Great Exception, as his newest miniseries comes with a jaw-breaker of a title that sounds like a piece of summer crossover from a stranger and much more literary world than our own.

This volume begins the third major “[[[League of Extraordinary Gentlemen]]]” story – last year’s [[[Black Dossier]]] doesn’t quite count, for complicated Moorian reasons – and it continues with the survivors of the team from the first two stories (Mina Harker and a rejuvenated Alan Quatermain posing as his own son), augmented by several more fictional characters (Orlando, Raffles, Carnacki) to continue their work preserving England from obscure horrors, reporting in to the secret group headed by Mycroft Holmes.

There will be two more volumes in this story – each set in, and titled after, a different and widely spaced year in the last century – so 1910 is mostly set-up. Moore re-introduces the League and sets them to squabbling, since superteams must always fight among themselves. The battling is less ominous this time around: none of the team are as immediately dangerous as Mr. Hyde, nor as sneakily obnoxious as the invisible Mr.Griffin. (So we get Raffles’s sniffing attempts to maintain his requisite stiff upper lip in circumstances he never expected and Orlando engaging in high-quality mincing whenever the slightest opportunity arises, along with Mina’s usual Serious Girl act and very little from the increasingly colorless Alan.)

Elsewhere, on his mysterious island, the aged Captain Nemo is dying, and having an presumably long-standing argument with his young, nubile daughter Janni. She disagrees with whatever it is he says – the argument is all in Hindi (or in devnagari script, at least), so this reader was unable to discern the details – and runs away from home. Afterwards, it’s clear that the argument was about Janni taking over for Nemo after his death: he was in favor of it, but she was strongly opposed. She comes to London and gets a job washing up in a seedy portside tavern/hotel, where she is watched lecherously by the locals, and called Jenny Diver.

Meanwhile, the League goes chasing after the source of a dream Carnacki had – in which the thought-dead occultist Oliver Haddo cackles about his fiendish schemes – since they have the vague sense Haddo’s schemes will lead to some kind of armageddon, eventually. They attend a meeting of the Merlin Society, meet a man unstuck in time, and discover that Haddo is not only not dead, but quite powerful and leading a circle with nasty long-term plans, but don’t actually do much.

All the while, Janni’s story continues in parallel, narrated in Kurt Weill songs by Jack MacHeath and an older woman named Suki who frequents the establishment where Janni works. (I believe all of those songs are from [[[The Threepenny Opera]]], which provides Moore with much of the plot for this volume.)

Eventually, Janni has what would be an origin for a superheroine, the two plots finally intersect, and things get interesting. (“Interesting” in the fake old-Chinese sense of extraordinarily dangerous and violent.) But then it all dies back down immediately, with a “this isn’t over” speech from Mina and a big song-and-dance number from MacHeath and Suki to close it all out – this is only the first third of a trilogy, after all.

At the end of 1910, some readers will inevitably wonder why Moore didn’t just adapt The Threepenny Opera to comics directly, if that was the story he wanted to tell. (Others may wonder why those characters are in London, or what a 1928 play has to do with the year 1910.) This reader wondered why Moore seems to treat MacHeath (a vicious multiple murderer whose only redeeming trait is his singing voice) as an admirable figure, and whether these seventy-odd pages will turn out to be merely prologue to the story in the next two volumes. 1910 is stylish and exciting, with great Kevin O’Neill vistas of terror and wonder, but it doesn’t really tell a whole story. It’s not the mess that Black Dossier was, but the self-indulgence meter is tending upward, especially the longer that Orlando is left to babble on. But this is meant to be the beginning of a story, so it would be churlish to complain that it is a beginning. I wonder how many of these elements will prove to be important in the next volume – set more than fifty years later, in 1968 – but, for that, we all will just have to wait and see.

Andrew Wheeler has been a publishing professional for nearly twenty years, with a long stint as a Senior Editor at the Science Fiction Book Club and a current position at John Wiley & Sons. He¹s been reading comics for longer than he cares to mention, and maintains a personal, mostly book-oriented blog at antickmusings.blogspot.com.

Publishers who would like to submit books for review should contact ComicMix through the usual channels or email Andrew Wheeler directly at acwheele (at) optonline (dot) net.

Okay, Setting any part of "Threepenny" in 1910 is a Bit Odd, since major parts of the plot revolve around Victoria's coronation.I wonder if the songs are actual "Threpenny" songs, since i would assume that it's still in copyright; certainly the Blitzstein adaptation is, and when they wanted to do a new translation/adaptation* for Shakespeare in the Park in the 70s (80s?) (with Raul Julia as Macheath), they had to clear it with Weill's widow, Lotte Lenya (the original Jenny Diver, BTW).*I suspect that the reason it was felt a new adaptation was needed is that the Blitzstein version is believed (wrongly) to be a bowdlerisation; in actuality, it was Mike Curb at MGM Records who insisted on extensive cuts and rewrites in the lyrics when the Original Cast album was recorded. (Another Fascinating Fact: That OC album features John Astin and Paul Dooley as two of Macheath's men, and Bea Arthur in a major role…)

I haven't seen this comic yet, but -The Threepenny Opera was based on an even earlier musical called the Beggar's Opera. From the 18th c., it had a Macheath, Polly, Jenny, Suki, etc. Could this be what Moore is referring to in his 1910 storyline? http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Beggar%27s_Opera(not that he wouldn't shrink from subverting the very fabric of space-time, but , y'know …)

That's a nice theory, but…the internal title of this story is "What Keeps Mankind Alive," and that's clearly a reference to the Brecht/Weill version of the story.

That's the "Second Threepenny Finale" (i think) – the first and second acts end with songs sung in front of the curtain by characters; it's pretty well breaking the fourth wall because they're basically singing directly to the audience.And to drive home the moral of the song, that one is sung by Macheath and his mother-in-law (more or less) Mrs Peachum, who, with her husband runs a protection racket among London's beggars, and is trying to get Macheath arrested and hanged so that they can marry off her daughter, Polly, to some rich old Lord:Mrs Peachum sings:you warn us, with appropriate caressesthat virtue, humble virtue, always winsnow please, before your moral fervor presses,our middle's empty – there it all begins!all you who dote on our despair and your desiremay learn the simple truth from this our song – whatever you may do, whatever you aspire, first feed the face – and then talk right and wrong!for even saintly folk may act like sinnersunless they've had their customary dinners!spoken, by Macheath:what keeps a man alive?what keeps a man alive?he lives on othershe likes to taste them firstthen eat them whole if he can!forgets that they're supposed to be his brothers …that he himself was ever called a man!remember, if you wish to keep alive -for once do something wrong, and you'll survive!=================(Called "How to Survuve" in the Blitzstein version)

Doubt it; "Beggar's Opera" was a satire of the current Government – Walpole's, i think, while "Threepenny" is basically a Marxist attack on bourgeois capitalism and the complacency of the mddle class.Brecht and Weill sound more like people Moore would be referencing than does Gay.(BTW: The original "Beggar's Opera" was quite popular in its day – the impresario who ran the theatre/company where it was staged was named Rich – and it was said that "The Beggar's Opera"'s success "…made Gay rich and Rich gay."

I would have liked more review and less summary.

http://forbiddenplanet.co.uk/blog/2009/talking-to…Its Threepenny.

I thought the comic was really good, full of references to culture, literal and musical, and the Threepenny songs are not literal to their real versions, but they evoke the same feeling. Although I know more of Mack The Knife from Sinatra, as much people do, so I kinda heard the Sinatra's tune, with a raspy voice for MacHeath, when I read his songs. But, the song that MacHeath sings in the gallows, is that a counterpart of a Threepenny song? I don't know, maybe it is, if it is, can you tell me what song?