John Ostrander: No Trespassing

My Mary will sometimes pop into the office to chat a bit. If I’m just goofing off (a lot of my work day consists of goofing off), that’s fine but if I’m actually working she has to leave. She understands and doesn’t take offense; she can get the same way when she’s creating.

I don’t want anyone looking over my shoulder when I’m working, especially with the initial draft. I get self-conscious and everything freezes up and goes away. Oddly enough, Kim didn’t always understand that. It bothered her that there was a private place inside me to which she was not invited. She felt a couple should share everything and, for the most part, I agree – except when I’m writing.

I suppose that, with most couples that’s also true to some degree. Perhaps it’s even desirable that the person with whom you’ve spent a good long time can still surprise you, hopefully in positive ways. I once wrote a Wasteland story in which the husband challenges his wife when she claims she knows him completely. He suggests that he could, in fact, be the serial killer they’ve heard about. The claim that he could be eats away at his wife and, by the end of the story, she’s ready to leave him because she realized that the doubt she is feeling indicates she doesn’t really know her husband at all.

It is a big question. How much do we really know another person – even someone that we know intimately? We start off the relationship by being attracted to someone which may lead to falling into what we think of as love. I would suggest that, in fact, what we’re really falling in love with is our construct of the person. Someone we’ve invented that’s based on the other person but is as much or more really based on us as it is them. Hopefully, as time goes by, our perception deepens as we see more of the actual person and, again hopefully, fall into more of a true love.

That gets chancy. As you wind up really seeing more of the other person, you have to let them see more of the real you. Brrr! Pretty scary, boys and girls! It does necessarily involve opening up.

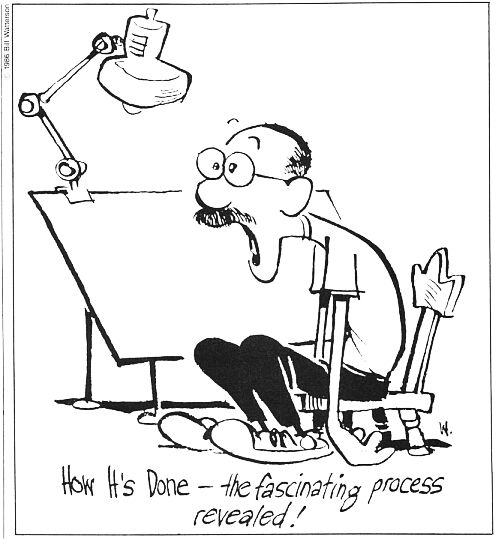

However, when you’re doing something creative – writing or art or what have you – the process can be very private. It’s a mysterious business to begin with; you don’t always know where the initial impulse comes from and you may not want to know. For a long time, I resisted any idea of going to a therapist because I felt that, if I knew more about my creative instinct, it would vanish. In reality, therapy turned out helping quite a bit. I understood why I did or thought some things and that understanding actually helped me creatively.

Still, I don’t want someone watching me create. I may need to dig around in parts of my psyche that can get a bit dark. (Those of you familiar with my work can probably appreciate that.) Nietzche said in Beyond Good and Evil: “He who fights with monsters should be careful lest he thereby become a monster. And if thou gaze long into an abyss, the abyss will also gaze into thee.” Kim and I used to describe the creative process as bungee jumping into the abyss and pulling out something. Usually it’s squirming.

I don’t need observers when I do that.

I do wind up revealing aspects of myself in my writing; you have to. Every character you write must in some way be you. However, you’re in disguise; you can always claim a given aspect of a given character is that character and not you. Keep in mind, as I’ve warned some people in the past, that I may appear to be a nice guy but GrimJack comes from somewhere in me.

And visitors are not welcomed there.

I just returned from a week’s vacation out in the sort-of-middle-of-nowhere, and it was glorious. Being my first long non-family or -convention-related vacation in ten years, it gave me some much needed down time to, e.g., work on my non-journalistic writing (along with spending time with a wonderful friend and meeting new friends, reminding myself anew of how terrible I am at watercolor painting, reading the exceptional journalistic work of Ernie Pyle, getting a tad bit in shape, listening to excellent music really loudly through gorgeously immense speakers, stepping out into the sun more than I usually do in my office-bound work, and, you know, actually relaxing a bit).

I just returned from a week’s vacation out in the sort-of-middle-of-nowhere, and it was glorious. Being my first long non-family or -convention-related vacation in ten years, it gave me some much needed down time to, e.g., work on my non-journalistic writing (along with spending time with a wonderful friend and meeting new friends, reminding myself anew of how terrible I am at watercolor painting, reading the exceptional journalistic work of Ernie Pyle, getting a tad bit in shape, listening to excellent music really loudly through gorgeously immense speakers, stepping out into the sun more than I usually do in my office-bound work, and, you know, actually relaxing a bit).