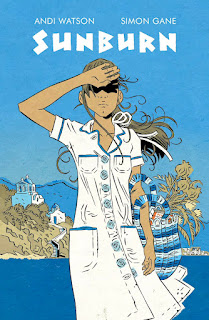

Sunburn by Andi Watson and Simon Gane

Andi Watson is a criminally underrated maker of comics. He’s done great work for almost three decades now, but I never see him included on the list of greats. Maybe it’s because he never dabbled in the core Wednesday Crowd (is it still Wednesdays? I lose track, and the big day was Friday way back when I cared) comics – the closest he’s ever come is Love Fights , a relationship story set in a superhero universe.

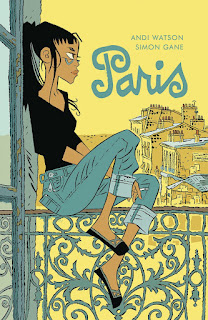

I don’t know Simon Gane’s work as well, but what I’ve seen has been impressive – lush, illustrative pages with style and energy and a clear viewpoint. His Paris , with Watson, is particularly impressive.

So I don’t know how many people were eagerly awaiting their second collaboration, Sunburn , but I was definitely one of them. And the book does not disappoint.

It’s another historical, like Paris. To my eye, it’s set at the beginning of the ’60s, but it could be slightly earlier – there are mostly ’50s cars on the streets, but two-piece bathing suits are generally accepted. (The very first panel is a view of the main character’s room, with a lot of little signifiers – James Dean, some group with guitars I’m not 100% sure of, a record player – to help immerse the reader. Watson and Gane work a lot like that: unobtrusively but clearly showing rather than telling.)

Rachel is sixteen, the only child of a suburban British couple. Her parents seem to be perfectly nice people, a little staid but loving and happy. She unexpectedly gets an invitation, from a business acquaintance of her father’s, to spend the summer in Greece – and that’s the story here, so she accepts.

Close readers will wonder at this to begin with: the connection is very thin, and the invitation is out of the blue: who is this couple, and why are they inviting a sixteen-year-old girl they really don’t know along on vacation with them? Sunburn will explain this all, eventually.

But Rachel does not question her good fortune. She arrives quickly in sunny Greece – exact island and location left unspecified; this is a story about people and maybe the contrast between England and Greece, not about a specific place or historical time – and settles in with Diane and Peter, who are more stylish and young-appearing and sophisticated than she expected. They are friendly, they treat her like their daughter – or maybe a younger sister – and they introduce her to the life of this island, giving her fancy clothes to wear to the regular cocktail parties of their (seemingly quite affluent) set.

Among those introductions – well, central to those introductions – is a young man named Benjamin, whom Diane not-all-that-subtly puts together with Rachel. Again, a perceptive reader will start to think something is going on, and will learn more later.

Sunburn is the story of that place, that summer, and those four characters: Rachel at the center, her relationships with especially Diane and Ben, and Peter in a more distant orbit. I won’t tell you what happens, or why Rachel was invited, but I will say this is a subtle story rather than a brash one, a story about people and relationships.

Watson and Gane tell that story quietly, through gesture and glances as much as anything else. The style is somewhat cinematic; Sunburn is the kind of graphic novel that could be adapted into film without too many changes. And they tell a deep, resonant, grounded story: I didn’t see this until the new year, but it was clearly one of the best books of ’22.

Reposted from The Antick Musings of G.B.H. Hornswoggler, Gent.