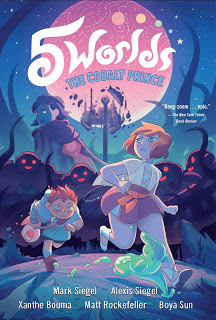

Book-a-Day 2018 #174: 5 Worlds, Book 2: The Cobalt Prince by Siegel, Siegel, Bouma, Rockefeller & Sun

I don’t read enough books aimed at kids to really know the shapes of subgenres these days, and so it’s dangerous for me to speculate. But I’m pretty sure the 5 Worlds series is not the only graphic novel series these days marching down the trail that Kazu Kibuishi’s Amulet series blazed.

I’m not saying that to point a finger: the opposite, in fact. I think there’s a whole bunch of books like this: fantasy adventure stories for middle-grades readers, told in graphic novel form, with groups of spunky kids and their quirky adult allies racing to save their entire, weirdly-constructed worlds from some manner of Dark Lord that particularly resonates with kids.

What I am saying is that I won’t be able to explain the places the 5 Worlds series breaks away from that subgenre, and what ways it’s faithful to it. I can only say that I see a dim territory stretching out behind this book, full of other wonders, and then describe what’s right in front of me.

What is right in front of me is the second book in that series, The Cobalt Prince . (I didn’t see the first one, The Sand Warrior.) It’s co-written by brothers Mark Siegel (Editorial Director of First Second and cartoonist of the excellent graphic novel Sailor Twain ) and Alexis Siegel (writer and translator of various things, including Joann Sfar’s The Rabbi’s Cat), and drawn by a team of three: Xanthe Bouma, Matt Rockefeller, and Boya Sun. Neither the book itself nor the cover letter explained how the three divide art duties, so insert a graphic of me shrugging here. Maybe it’s the old pencil-ink-color, maybe it’s figures-backgrounds-finishes, maybe they all work in the same style on different pages, maybe something entirely different.

Our Chosen One this time is Oona Lee, a preteen girl who is one of only two Sand Dancers — the particular kind of magic used in this universe — who can call the Living Fire. Our universe is made up of five worlds: it seems to be one large planet and four moons, all habitable. (I don’t see how that can be possible, but this is not hard SF.) Each planet has a magical beacon which can only be lit by the Living Fire, and Oona believes the beacons of all five worlds must be lit to make everything right. (It is not hugely clear in this book exactly what was not right, though there is a big evil thing called the Mimic lurking around and threatening everyone.) In the first book, she lit the beacon of Mon Domani, the central mother world.

So, at the beginning of this book, she’s off to the next world — Toki, the blue one, seat of a militaristic blue people — to light the next beacon, along with her friends Jax Amboy (a popular professional athlete who is secretly an android) and An Tzu (who is slowly disappearing because of some mystical disease which will definitely be plot-important).

Possibly new in this book is Oona’s long-lost older sister Jessa, who went away with the Toki people when Oona was very young, Jessa has since become blue, like the Toki people, lost her ability to call the Living Fire and may have been ensnared by a body-possessing spirit of evil called the Mimic (the Dark Lord of the series).

There are shocking revelations, several Everything You Know Is Wrong moments, lots of magical and physical battles, at least one noble sacrifice, and one character coming back from what seems like certain death. It’s a good adventure story in this middle-grade mode, and will be very appealing to fans of Amulet or The Last Airbender (which seems to have seriously influenced the magic system here). Its appeal to adults is not quite as strong; we’ve seen things like this many times before. But it’s good at what it does, has nicely rounded, attractive art, and delivers on what it promises.

![]()

![]()

Reposted from The Antick Musings of G.B.H. Hornswoggler, Gent.