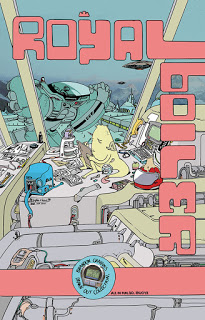

Glenn Ganges in: The River at Night by Kevin Huizenga

I always feel compelled to begin by stating for the record that Glenn Ganges is not Kevin Huizenga. Of course, he’s not Ganges the same way Sal Paradise is not Jack Kerouac — the old fictional yes-but-no-but-yes two-step.

Ganges has been a main character in most of Huizenga’s books I’m aware of: Gloriana and The Wild Kingdom and Curses . No wait. I don’t mean “main.” I mean “viewpoint.”

That may sound like a nitpick. Describing the stories of Kevin Huizenga will lead to a lot of nitpicks, and descriptions of nitpicks, though — it’s inherent in the territory. Glenn Ganges is a man living in a secondary American city (maybe St. Louis, where Huizenga used to live, or Minneapolis, where he does live now), married to Wendy (I can’t find any references online to Huizenga’s personal life, and won’t speculate), and working some kind of tech-adjacent office job (again, I don’t know what Huizenga does to pay his mortgage and put food on the table, though a graphic novel every few years probably isn’t it).

But the reader gets the sense that Ganges is mentally an avatar for Huizenga. Huizenga’s comics are about thoughts more than actions, ruminations more than activity, knowledge more than thrills. It’s not quite true that his comics all take place in Ganges’ head, but that’s not a bad simplification.

The River at Night , similarly, is not the story of one night when Glenn just couldn’t fall asleep. That’s a framework for much of the book, true, but it ranges more widely than that — even leaving out the geological time and personal history and pure formalist cartooning that comes up during that one long, restless night.

A book like this relies heavily on two things: its creator’s visual inventiveness and intellectual curiosity. Huizenga has both in industrial quantities, seemingly inexhaustible supplies of startling imagery and complex thoughts, and he rolls them out in waves throughout River at Night, interspersing formalist comics experiments of two muating forms fighting (or whatever) in a video-game space with flashbacks to mundane life and long scenes of Ganges lying in bed thinking or wandering his house ruminating.

Huizenga’s art is on the cartoony side, with dot eyes and simplified limbs for his people, and he uses a cool night-blue palette for most of this book, with only a few sunset- or sunrise-desaturated pinks at appropriate moments. That visual simplification — or concentration, perhaps — lets him focus on the ideas and their visual representations; he doesn’t need to draw every line in Ganges’s hair when a calendar is exploding into deep time.

There is no real story to The River at Night. I’m not going to tell you “what happens” — that’s not the kind of book this is. It’s a dizzying, mesmerizing, deeply specific meditation on life and time and purpose and meaning. It’s both accessible in a way I didn’t always find Huizenga’s earlier work — leading into the deep thoughts in measured steps, looping in and out of obsessions to illuminate them from multiple angles — and thrilling in its audacious energy. I can’t guarantee it will make you think about things differently…but if a book like River at Night can’t make you think, I don’t know what can.

![]()

![]()

Reposted from The Antick Musings of G.B.H. Hornswoggler, Gent.