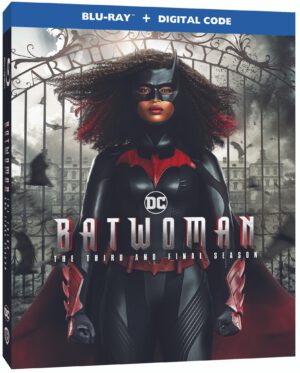

REVIEW: Batwoman: The Complete Third Season

From the outset, the CW’s Batwoman series was one of the better offerings, thanks to a strong visual sensibility and a winning performance from Rachel Skarsten as the damaged Alice. And like every other Arrowverse show, it threatened to suffer from character bloat by the end of its second season. Thankfully, supernumerary characters and plot points were jettisoned and Javicia Leslie, as Ryan Wilder, made Batwoman her own character after Ruby Rose’s departure.

Season three, therefore, offered a lot of promise and across thirteen episodes we saw the show flirt with good, solid storytelling, too often succumbing to mind-numbing plot holes and illogic. It suffered from being hampered by the idiotic notion that Circe could waltz into the Batcave and make off with Batman’s greatest rogue weapons, all neatly fitting into a duffel bag.

We open with Renee Montoya (Victoria Cartagena) blackmailing Batwoman and Alice into tracking down and recovering these deadly weapons. As a result, the first half of the season has them chasing around to collect things like Mad Hatter’s hat and Mr. Freeze’s gun.

The real drama is the revelation that Ryan Wilder’s birth mother is located and she turns out to be CEO Jada Jett (Robin Givens). They snap and verbally spar with one another until all the rough edges are sanded off and they become allies, even friends, draining the drama. Instead, the season’s real threat comes from her son Marquis Jet (Nick Creegan), who is jealous and unstable, evolving into Batwoman’s Joker. His ultimate threat is straight from the 1989 feature film and pales in comparison.

The problem, of course, is that it reduces the need for Alice to be the crazy one on the show. She, instead, befriends Mary (Nicole Kang) and they go on a road trip as Mary is infected by Poison Ivy and she kills, a traumatic issue that carries her for the remainder of the show.

Supporting everyone while working through his own issues is Luke Fox (Camrus Johnson), who desperately wants in on the fun as Batwing but has the psychological block of wanting his dead father’s approval. Also running around is Sophie Moore (Meagan Tandy), seeking a place post-Crow life, seeking comfort first in Montoya’s arms, then finally getting it on with Wilder, making them a power couple.

There are plenty of interesting moments for each character, but the collective thirteen episodes are more mess than compelling drama. A stronger season arc without the need for a faux-Joker, a corporate battle between mother and daughter overlayed atop a serious threat, would have been far better.

The season ended with a hint of more danger to come but in a wholesale change of direction, the show was canceled along with other DC series. We now have the three-disc Blu-ray set, complete with DVD and Digital HD code courtesy of Warner Home Entertainment.

Every episode is included along with a handful of Deleted Scenes, a short Gag Real, and a featurette: Batwing: A Hero’s Journey.