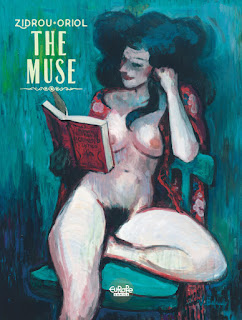

The Muse by Zidrou and Oriol

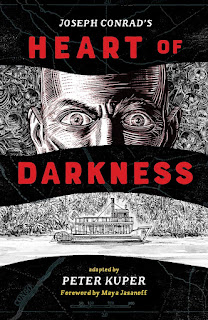

If that cover image trips any warnings on whatever computing device you’re reading this on, I apologize – but it is the cover for this book.

The Muse is an album-length graphic novel, written by Zidrou, drawn by Oriol, translated by Matt Madden, and published – only electronically; there’s no print version in English – by Europe Comics a few years back. It’s the story of a painter over a hundred years ago, as told by a painter about eighty years ago, doubly distanced.

In the very last days of the nineteenth century, Vidal Balaguer was one of the most talented of the painters of Barcelona – but also in the worst troubles. His father has recently disowned him, so his debts are mounting. The woman who was both his best model and his lover, Mar, has mysteriously disappeared and the police suspect he may have killed her. And the one painting he might be able to sell is his masterpiece of Mar – the one that is the cover of this book – which he can’t bear to part with.

One of his friends tells this story, to another model, forty years later, in a frame story that disappears for most of the book and is not important at the end: it’s a way in rather than a full frame, and I’m not completely convinced it actually adds anything to the core story of Balaguer. I even lost track of which one of the 1899 friends this old painter was supposed to be, since he doesn’t do anything important in the Old Days.

Balaguer is beleaguered – maybe the word is similar in Spanish? I don’t know if this is deliberate, on Zidrou’s part or Madden’s. Things are disappearing from his apartment. Creditors are circling, threatening to take everything he has. A police detective threatens even more.

There is an explanation, and this reader guessed it – and Balaguer’s way out of his situation – much sooner than the book revealed it. I can’t say if that is a common reaction; I’ve been that kind of reader for thirty years or more , always picking apart the stories I encounter and predicting where they will go next. I’m not always right; I was this time.

Oriol has suitably painterly art for this story; the spaces are deep and rich and evocative , the people subtly color-coded, the action mostly interior. Zidrou gives it a leisurely, talky script – these are mostly painters with time to waste in cafes or scraping paint onto a board – but reading it electronically (on a tablet screen, in my case) makes the balloons and lettering smaller than I would have preferred.

I did not find this a surprising story, or a profound one, though I did enjoy the telling. Zidrou may have aimed at surprise or profundity; I can’t say. In the end, there’s no real sense of why this happened to Balaguer rather than any of the other painters in his circle: was he better? was it his connection to Mar? was it just the luck and frisson of a moment?

Muses are fickle by nature, of course. Maybe that’s the answer.

Reposted from The Antick Musings of G.B.H. Hornswoggler, Gent.