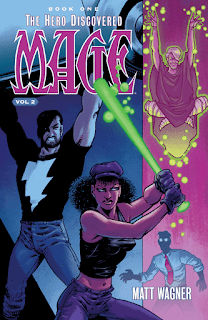

Book-A-Day 2018 #305: Mage: The Hero Discovered (2 vols) by Matt Wagner

I’m pretty sure this has been published in one volume, at least once. But the current edition is two volumes, and that’s what I read. (Long before that, it was published as fifteen comic book issues, and I had those as well, before my 2011 flood. But all things must pass.)

“This” is the first volume of Matt Wagner’s epic transmuting-his-life-into-heroic-adventure trilogy Mage. Mage: The Hero Discovered was one of Wagner’s first major comics projects in the 1980s and was followed by The Hero Defined at the end of the ’90s and, eventually, by The Hero Denied, planned to wrap up by the end of this year.

Since that third volume is about to finish up, and I expect to read it, I thought I might as well go back for the first two: when a creator takes 15-20 years between installments, you can do him the favor of reminding yourself of the old pieces before coming to the new ones. So I re-read Hero Discovered this month (Volume One , Volume Two ), plan to hit Hero Defined next month, which should get me ready for the first Hero Denied collection…which I see was published a few days ago. (I doubt I’ll be able to hold off until the second half of Denied is published as a book in February, but I did skip buying all of the floppies, so maybe I will. As I get older, the appeal of story-pieces has gone down precipitously.)

Very early in the life of this blog, I had a breathless review of Defined , which I’m linking here for completeness’s sake — I really hope you don’t go back and read those burblings, which I am now embarrassed by. Otherwise, I’ve mentioned it, but not gotten into any depth.

It starts with overwriting two guys meeting on a city street — one may be drunk, and pretends to be happy, and one may be a bum, or pretends to be one. (Their dialogue is wince-inducing: if you decide to read Mage, you need to remember that it was nearly the first thing Wagner did in comics, and that he got better quickly — though ponderous unbelievable dialogue is an occasional hazard throughout the Mage stories.)

The not-drunk guy is Kevin Matchstick, who is so sad because he’s all alone. The not-bum calls himself Mirth, and he’s the mage of the title — there will be a different one for each series. Right after their conversation, Kevin sees a man attacking an actual bum in an alley, and surprises himself by running to intervene. He’s even more surprised to find the assailant is a hairless pale-skinned humanoid with sharp points on his elbows and that Kevin suddenly has super-strength and speed. The bum dies; the humanoid gets away.

And Kevin goes back to his apartment, confused, to find Mirth, who starts the official Hero’s Journey by explaining (well, a little) who he and Kevin are. Mirth is the World-Mage, opposed to the evil Umbra Sprite and his sons, the Grackleflints (the humanoids), who do the usual evil thing of corruption and destruction. Kevin has another fight with three (of five) of the Grackleflints in a subway car before he gets the next round of explanations from Mirth.

And Kevin goes back to his apartment, confused, to find Mirth, who starts the official Hero’s Journey by explaining (well, a little) who he and Kevin are. Mirth is the World-Mage, opposed to the evil Umbra Sprite and his sons, the Grackleflints (the humanoids), who do the usual evil thing of corruption and destruction. Kevin has another fight with three (of five) of the Grackleflints in a subway car before he gets the next round of explanations from Mirth.

I’ll be blunt here, though Kevin doesn’t find this out for a long time: he’s The Eternal Champion King Arthur kind-of King Arthur, in that he’s the latest incarnation of a mythic hero and was once little Wart. He will gather allies — a teenage girl with a bat and a dead public defender — and, together, they will help him battle the Umbra Sprite and all of the supernatural creatures that the Sprite can summon and throw at him. The Sprite is searching for the Fisher King — another reincarnation, though not a hero — and if his Grackleflints can kill the Fisher King, it will bring a new era of death and destruction to earth.

And that’s the story of Discovered: this is explicitly a Hero’s Journey book, so Kevin learns bits and pieces of the setup over about four hundred pages, punctuated with fights against dragons and giants and redcaps and other mythical beasties, and occasionally broken up by attempts to actually figure out what the forces of evil are doing, where they’re headquartered, and how to stop them.

Before the end, there are major sacrifices so the Hero can stand alone, quite a lot of epic fight scenes, and a surprisingly nuanced view of the relationships among the forces of evil. Wagner started this series a little shakily, but it had great bones right from the beginning, and both his drawing and writing skills got stronger very quickly. It’s unfortunate that the two very worst pages in the whole Mage saga are the first two, but at least you can know that going in.

Somewhere along the line, the original 1980s-era coloring disappeared and was replaced by a more modern treatment by Jeromy Cox and James Rochelle — I think this is from the Defined era, but don’t quote me. I should also note that Wagner is inked by Sam Kieth, starting with the sixth (of fifteen) chapters, and that lines up with one of several leaps forward in the strength of the art. (So it’s not all Wagner, as the cover makes it seem — very few comics are that much of an auteur medium; there’s always some collaboration going on.)

Mage is a strong urban fantasy story in comics form, clearly in a mythic vein but with a lot of individual touches. It’s classy enough to have titles from Hamlet (and never say so, or explain them), and street enough to be about the reincarnation of King Arthur beating up monsters to save the world. And, if you’ve been waiting for the whole Mage saga to be done, you are nearly in luck.

![]()

![]()

Reposted from The Antick Musings of G.B.H. Hornswoggler, Gent.