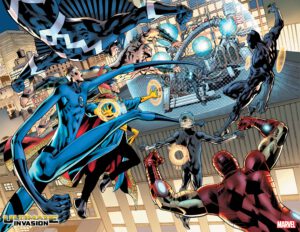

Hickman & Hitch Revive Ultmate Marvel

Two of the comic book industry’s most innovative and exciting creators are teaming up to reshape the Marvel Universe as you know it! This June, join writer Jonathan Hickman and artist Bryan Hitch in Ultimate Invasion, a revolutionary four-issue saga that presents a surprising new chapter for Ultimate Comics and bold new strides for Marvel’s iconic heroes.

Launched over twenty years ago, the Ultimate Universe provided a contemporary take on classic Marvel characters and storylines. Known for its edginess and explosive action, the Ultimate Universe was home to some of Marvel’s most talked about and thought-provoking series of the 21st century. The Ultimate Universe reached its cataclysmic end in 2015’s Secret Wars, but nothing stays buried in Marvel Comics for long. Is it time for the Ultimate Universe to make its grand return? The Maker seems to think so and the Illuminati must form once again to stop him from his plans to destroy – or perhaps rebuild – the universe, with Miles Morales at the center of it all!

Hitch’s work on The Ultimates helped redefine super hero comics for the 2000s and Jonathan Hickman has successfully invigorated the Fantastic Four, Avengers, and X-Men in the last decade. Wait until you see what these two powerhouse talents have in store next! The debut issue will include new data pages by Jonathan Hickman – plus exclusive behind-the-scenes material on the world-building that has gone into this project!

“[Revisiting the idea of Ultimate Comics] couldn’t be replicating or revisiting what Bryan did in the original Ultimates — creating a streamlined, modernized version that would eventually become the spine of the MCU, and it certainly couldn’t be what I did, which was a final chapter of a pre-existing universe,” Hickman explained to Entertainment Weekly. “We also thought the very idea of Ultimate Comics needed to be inverted from what the original universe was — we wanted this to be something that could really only exist in the comic space: a new way of thinking about, and enjoying, a new version of the Marvel Universe. I’m pretty happy to say that it feels like we’ve accomplished those things and we’re very excited for everyone to get to read it.”

“It’s been more than 20 years since I started work on The Ultimates, a project that would have a big impact on my own career and beyond, so when Marvel came to me with the idea of revisiting the Ultimate Universe with the man who so brilliantly and spectacularly destroyed the last one, I was both feet in!” Hitch said. “Jonathan is a terrific writer of big, sprawling epics, and we’ve talked about working together more than once so for this new Ultimate Universe adventure to unite us is very exciting. I get to bring two decades of new experience as an artist and storyteller to this. It’s new, different and familiar. It’s big budget, high-concept, widescreen storytelling. I feel right at home.”