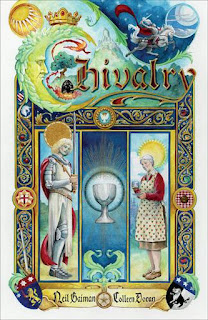

Chivalry by Neil Gaiman and Colleen Doran

Stories about old people who are happy and content being old, who stoutly resist fantastic temptations otherwise, are I think always the products of much younger people. Actual old people are much less sanguine about looming death, I find, less likely to smile indulgently at mantlepiece pictures of themselves in their younger days, sigh contentedly, and turn their faces away from mysterious elixirs and fabulous potions.

Neil Gaiman was barely thirty when he wrote the short story “Chivalry” in the early 1990s. It’s a light, mostly humorous story. But it’s very much the humor of someone quite young looking at someone else who is quite old, at a light, humorous distance.

Chivalry was turned into a graphic novel recently – just about a year ago – by Colleen Doran, who apparently scripted this version as well as doing all of the art in a variety of styles. (Lettering is by Todd Klein. There’s no sign Gaiman did anything for this edition other than say the word “Yes” and sign some manner of document.)

Lots of Gaiman stories have been turned into individual GNs over the past decade or so – I count a dozen on the “other books” page here, plus multi-volume adaptations of American Gods and Norse Mythology – but he’s probably written close to fifty stories in prose [1], so the well will not go dry any time soon.

This is one of the lighter – I’m pointedly not saying “lesser,” but we’re all thinking it – stories, though Doran brings a formidable, and frightening, level of art firepower to this piece, depicting some pages as medieval illuminated manuscripts and explaining in an afterword the extents she went through to find photos of the actual rooms of the real house Gaiman was thinking about for his protagonist back thirty years ago. (One might think that’s all rather more effort than Chivalry required, but it’s not for us to say, is it? The final product is indeed lovely throughout.)

So: pensioner Mrs. Whitaker finds the Holy Grail in her weekly trip to the Oxfam shop in the high street. She knows exactly what it is, and that it will look nice on her mantlepiece. Soon afterward, the parfait gentil knight [2] Galaad arrives, asking politely if he may have it, since he’s on a quest from King Arthur, with a fancy scroll to say so.

Gaiman, as usual, is not doing the collision of high and low speech thing, as other writers might. Galaad is high-toned, and Mrs. Whitaker is sensible and middle-class, not some comic-opera Cockney. They have polite, friendly conversations, with no hint of drama or conflict. Mrs. Whitaker simply wants to keep the Grail; it looks nice where it is.

Galaad returns several times, with more-impressive gifts to entice Mrs. Whitaker. What he does not do is listen to her, ascertain what she wants, and try to deliver that – that would be a more serious story, and not the one Gaiman apparently wanted to write in 1992. Galaad just wants to find the thing that will get her to agree to a swap, and he does, in the end, since this is a light fantasy story.

The prose “Chivalry” was a pleasant quiet thing, all about what wonderful characters the plucky elderly British ladies of the war generation were, basically a love letter to Gaiman’s grandmother’s cohort. The graphic version keeps the tone and style, and adds a lot of very pretty art, some of which is incredibly fancy and detailed. It is still a very light, fluffy thing, which only very slightly connects to actual life, but this is a very good visual version of the thing this story always was.

[1] It’s difficult to count, since his collections differ by country and mix in a lot of poetry, and he’s also done a lot of chapbook and small-press publications over the years. When you’re the subject of a rabid fandom, you can publish in all sorts of complicated expensive ways and people still buy as much as they can.

[2] OK, Gaiman doesn’t actually phrase it that way. But it is still true.

Reposted from The Antick Musings of G.B.H. Hornswoggler, Gent.