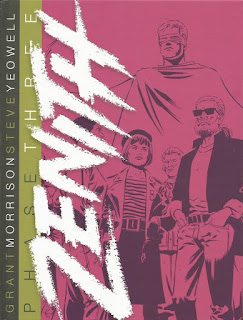

Zenith: Phases One to Four by Grant Morrison and Steve Yeowell

Zenith is quite likely the best possible revisionist superhero comic series told in five-page chapters. That sounds like damning with faint praise, and there’s an aspect of that — those short chapters put Morrison and Yeowell’s work in a straitjacket that they can never get free from, denying them all but the most absolutely necessary splash pages and forcing every installment to move forward quickly and efficiently — but it’s still an impressive achievement, and a pretty good revisionist superhero in general. His stories originally ran in the UK comics magazine 2000 AD, in weekly installments between 1987 and 1992, which explains the five-page-chapters issue. All the stories were written by Grant Morrison, at that point the current snotty Young Turk of British Comics, and drawn by Steve Yeowell, who had no such easy hook to be hung on and so had to get by on hard work and talent. (Not that Morrison was lacking in either of those.)

Zenith supposedly is a slacker superhero, and these stories are old enough that Generation X (my generation) was the one filled with young lazy layabouts who couldn’t be bothered to work — whereas now we know that really describes millennials, who have the bad grace to be young now, when so many of us are sadly no longer so. (We may all know different in another twenty years, but we’ll need to think up a new derogatory nickname for yet another generation first.) Zenith isn’t really that much of a slacker; he does hesitate initially to jump into the big superhero plot of Phase One. but that’s over very quickly (no room for Hamlet-esque equivocation in five-page chapters), and he’s flying around and punching monsters almost immediately.

Phase One quickly introduces us to what we need to know, with a prologue of this world’s end of WWII: the Nazi superhero Masterman is about to kill the English superhero Maximan in Berlin when he’s temporarily stymied by a nuclear bomb that levels the city. (No spoilers: we see the not-dead Masterman by the end of the prologue in the modern day. As I said, short chapters means this has to move fast.) Fast forward two generations: there were a bunch of British superheroes in the ’60s, who broke free from government control, called themselves Cloud Nine, and eventually broke up. Half of them are now dead, and the three left alive have all lost their powers.

But two of the dead supers had a son, and that boy — Robert McDowell — is the 19-year-old pop star Zenith in the fateful year 1987. Zenith is self-centered and arrogant and the kind of prick that only the teenage international celebrity only-superhero-in-the-world could be. His agent tries to keep him on-task, poor man, but it’s clearly an impossible job. Oh, but here comes Masterman, reincarnated by a secret society that worships the Lovecraftian “Many-Angled Ones” from beyond space that which to come down and eat our souls. (As in Loveccraft, it doesn’t do to think too much about why cultists would want to destroy the entire world and have their souls eaten first.)

And it turns out that the three depowered superheroes are not as depowered as previously thought, and that Zenith will join the battle once we get through a few scenes of him being petulant and young and thick-headed. So Zenith and the most powerful of those remnant ’60s heroes — Peter St. John, a powerful telepath and hippie-turned-Thatcherite PM — defeat Masterman and the thing from beyond space that inhabited him, saving the world and paving the way for St. John’s ascension to running the Defense Ministry.

There are, of course, Dark Hints about Zenith’s parents, which come out in Phase Two

There are, of course, Dark Hints about Zenith’s parents, which come out in Phase Two. This one is the least cosmic of all four Phases, with a Bond-villain-style mad billionaire who has bankrolled the creation of new supers — though a connection with the One Scientist that created all of the UK’s supers for three generations [1] — and plots to destroy the current world with nuclear fire and build a new one with his pet superhumans. Zenith needs the help of a CIA agent and (once again) St. John to foil this one, but of course it is foiled in the end.

As usual for events that supposedly killed entire super-teams, we learn by this point that hardly anyone in Cloud Nine actually died or was depowered in the ’60s. Half of the team fled to one of the infinite alternate worlds — this might be the first time Morrison uses that idea, so Morrison fans take note — as part of a larger Plan, which the three left behind (St. John and the two that don’t do much) didn’t want any part of. But that’s still to come.

Phase Threeis the big, gaudy Crisis of the Zenith universe, with supers from dozens of worlds gathering together with Zenith and St. John under the leadership of an alternate-universe Maximan to defeat the Llogior. (The Lovecraftian Many-Angled Ones having quietly rebranded themselves at some point while they were offstage in Phase Two, they will be known under this name from now on.) Zenith even meets his nice, heroic counterpart from another universe, Vertex, which allows for some tension near the end.

And, yes, the collection of superheroes vaguely familiar to British audiences of the late ’80s — and much less so to this American, or to anyone not deeply steeped in UK comics of the ’60s and ’70s — does save the multiverse, although some fall tragically along the way, to make it more meaningful. (And there’s at least one shocking betrayal, for the same reasons.) But Zenith has very little to do with it; he’s there, and he does punch a few things, but that’s about the extent of his involvement.

Finally, Phase Four came along after a two-year gap, and introduced color to the series. (I’m not sure if this is because 2000 AD finally went all-color around 1992, or if it had a color section for a while and Zenith was at that point considered worthy, or what. But this Phase is in full comic-book color, while the first three are pure Yeowell ink.) Now the Big Plan of the surviving members of Cloud 9 comes to fruition, and of course it has to do with conquering the world and the Lloigor and all the things every Zenith story is about.

And, once again, St. John is the one who actually saves the world, while Zenith is mostly just around for the ride. Morrison did continue to hint that St. John wasn’t what he seemed — hints that go all the way back to the final pages of Phase One — which would imply that a Phase Five would finally see Zenith battle St. John. (This is very much a minimalist superhero universe, despite the multiple universes in Phase Three; everyone comes from the same origin, and they keep fighting and killing each other — eventually, obviously, the last two standing will have to fight in the final battle.) But there never was a Phase Five; the Phase Four book ends with a late-Morrison mash-up story from ten years later that throws all of the toys up in the air and delights in the weird shapes they make coming down. There’s no sign that Morrison and Yeowell ever will, or could, continue this story in a conventional way: this is what we have, and this is all there ever will be.

As I said a thousand words or so ago, Zenith is inherently handicapped by being told in five-page chapters. Morrison was lucky enough to be writing in a time and for a magazine that was happy to have lots of captions, so he’s able to tell larger, more complex stories than you might expect given that scope — but, still, every chapter has to have a shape, and has to have some action or tension to close it, and that gives Zenith an inherently herky-jerky cadence, with confrontations and fights coming at predictable intervals and never lasting very long.

Yeowell is also handicapped by the space: there’s only so much superhero action you can draw when you need to have ten panels and at least that many captions on each page. He does get more than his share of striking images out of Morrison’s concepts, though, particularly in Phase Four (perhaps because the rising tide of the ’90s was privileging pictures over captions).

So this is another flawed masterpiece, much like its model Miracleman. I imagine that amuses Grant Morrison to no end.

[1] This is very much like Emil Gargunza, from Alan Moore’s slightly earlier Marvelman/Miracleman stories. The backstory of Zenith in general bears a lot of resemblances to Moore’s worldbuilding; Morrison substituted Cthulhu for Warpsmiths, pretty much, and went forward from there.