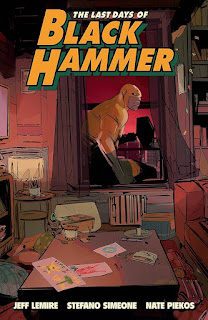

Black Hammer: Visions, Vol. 1 by Jeff Lemire’s friends

My standard complaint about the Black Hammer comics is that they’re mostly static, locked into an initial premise that wasn’t all that exciting to begin with. I suppose that’s in distinction to “real” superhero comics, which rely on the façade of change – someone is always dying, someone’s costume is always changing, someone is always making a heel-face turn, and worlds are inevitably always living and dying so that nothing will ever be the same – but it’s not self-reflective enough to count as irony.

But some kinds of stories aren’t supposed to change anything – the whole point is that they don’t, and can’t, change the things we already know. Jam comics by entirely different creators tend to fall into that bucket: they’re sometimes “real” and sometimes not, but even if they’re canonical, they don’t push the canon in any direction.

Black Hammer: Visions, Vol. 1 is a book like that – it collects four of the eight issues of the title series, each one of which was a separate adventure, by an entirely different team, set in the Black Hammer-verse. It’s all sidebar, all “I want to do this story” by people who will do only one Black Hammer story and this is it. So it’s self-indulgent in a somewhat different, more inclusive way than the main series.

Since the four issues here are entirely separate – and half of them have no credits within the stories themselves, making me wonder what comics editors do with their time if they can’t handle the most basic parts of their jobs – I’ll treat them each in turn.

Issue 1 has a story, “Transfer Student,” written by comedian Patton Oswalt and drawn by Dean Kotz, which is supposedly about Golden Gail but really is a light retelling of Dan Clowes’s Ghost World – I’m 99% sure Oswalt knew it was a comic first, and not just a movie – in the context of the pocket universe. This is pleasant and well-told and has decent emotional depth, but… We the readers know that the Enid character can never get out of this town: there’s nowhere else to go. She can’t go to college, find new friends, and have a different world to fit into. She is stuck in small-town hell, in the background of someone else’s depressive superhero story.

Oddly, the narrative doesn’t seem to know this. And that knowledge makes the reading of this story a substantially different experience than I think Oswalt wanted: this is a dark, depressing story with bone-deep irony, saying one thing and meaning the exact opposite.

The second issue sees Geoff Johns and Scott Kolins bring us “The Cabin of Horrors!”, a Madame Dragonfly-hosted horror tale. It features what could have been the sensational character find of 1996, Kid Dragonfly, and a nasty serial killer getting his comeuppance. This one feels the most like an actual random issue that could have been part of a larger comics line at the time – well, more like a Secret Origins retelling, cleaning things up maybe a decade later, but still in the same vein.

It’s a perfectly acceptable horror/superhero comics story, entirely professional and hitting all of its marks.

In the third installment, Chip Zdarsky writes and Johnnie Christmas draws “Uncle Slam,” the obligatory “I’m too old for this shit” story. The person too old for the shit is of course Abraham Slam; that’s been his main character note for the entire series. Here, he’s sixtyish, retired, running a gym and dating a woman who I think is meant to be a little younger than him but looks childlike (much smaller, very thin, drawn with a young face). But of course a new, more violent hero “takes his name” and he Has To Stand Up for Punching Evil the Right Way (Without So Much Death), which goes about as well as it ever does. He does not die, since he’s a superhero-comics protagonist, but other people do, and he loses a lot. The ending tried to move away from And It Is Sad, and would have been OK if this were a standalone story, but we know Abe gets back into the costume like five more times after this point, so it’s mostly pointless.

And in the last of these stories, Mariko Tamaki (of all people!) tells a story with Diego Olortegui art that I don’t think has a title. It’s a fun bit of metafiction, with our core heroes seen in multiple universes, as the viewers of and characters in and actors behind a popular TV show, with different relationships and interactions on each level. It is amusing, a fun exercise in moving the chess pieces around in unexpected but pleasant ways, but it doesn’t really turn into a specific story – it’s just a sequence of riffs on these characters and their interactions.

On the other hand, that’s the most successful and interesting thing in the book, so I can overlook the not-going-anywhere aspects.

So: all in all, it’s amusing and is pretty much what you would expect – random quirky takes on these characters and situations by other people, who each get to have one good idea for this setting and then go back to their real careers.

Reposted from The Antick Musings of G.B.H. Hornswoggler, Gent.