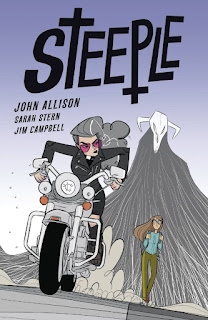

Steeple by John Allison with Sarah Stern and Jim Campbell

I have two theories about John Allison’s best stories, or maybe two versions of the same theory. One goes that his best works are organized around triumvirates – I should perhaps say triumfeminates – such as Bad Machinery and Giant Days , which allows the three main characters to bounce off each other in complicated ways. This theory goes on to say that the more straightforward, less convoluted Allison works are more likely to have two main characters (q.v., By Night ) who contrast each other in a more obvious way. [1]

The other theory is more straightforward: in every generation of Allison protagonists, there is a female character who embodies chaos, around whom reality itself sometimes bends, who is a force of nature, who both the complications of the narrative and the audience love. Shelly Winters, Charlotte Grote, Esther De Groot – that kind of character. The Allison stories that feature one of those characters are the best ones.

Steeple is a contrasting-two-people story, and neither of them (yet?) have risen to the level of an Allisonian Chaos Magnet. So I might perhaps say at this point that it’s not quite as zany as his best work, but that might also be said, in a different way, that it’s more accessible and less likely to hare off in random directions for no obvious reasons.

This story is set in the same universe as Tackleford – though, like Giant Days, it touches other parts of that world only very lightly. We are in the small town of Tredregyn, Cornwall – that’s in the far Southwest of England, for those geographically challenged, about as far you can get from Tackleford’s Yorkshire and still be in the same country. In Tredregyn, there are two churches. And, in each of those churches, there’s a young woman with good intentions.

Just arriving at the local parish – I think it’s CoE , and I think it’s St. something-or-other’s that only gets mentioned once in the book and which I can’t find now – at the beginning of the book is the new parson Billie Baker, to help out the Rev. David Penrose.

On the other side of town, there is a Church of Satan, run by Magus Tom Pendennis and Warlock Brian Fitzpatrick – though I had to look up their full names online; they’re just “Tom & Brian” in this book – where Maggie Warren does what she wilt as the whole of the law when she’s not slinging pints at the local pub. (First lesson: God pays better than Satan. Maggie needs a side job; Billie does not. Who knew?)

Billie and Maggie meet cute when Billie arrives in town, and become friends, even though their lives are deeply opposite to each other.

So that’s one major conflict: they’re friends but they work for (to put it mildly) competing organizations.

The other major conflict is weird supernatural stuff, as it often is in Allison: Tredregyn is in danger from a race of aquatic monsters who want to drag the town and surroundings back beneath the sea whence it came, and apparently they could be successful in this if the local priest doesn’t spend his nights punching said monsters in the cemetery. Penrose keeps asking for strong, burly assistants to aid him in biffing the salty foe, but his superiors keep sending him thin and weedy types. Like Billie, for example.

Now, those sea monsters are said to be sent from the devil, but they don’t seem, at least in this first storyline, to have any connection to the Church of Satan. So it may be that the devil has legions who know naught of each other, or perhaps the sea beasties are actually the spawn of Cthulhu or Belial or some different evil entity. Or perhaps the Church of Satan is the modern, free-living kind of Satanism, and has mostly or entirely sworn off actual evil in the sense of conquering the world and dooming souls to eternal torment and suchlike.

This first volume of Steeple stories – it doesn’t have a “Vol. 1” anywhere on it, though a second volume has since appeared, and a third is coming this summer – collected five comics issues, written and drawn by Allison with colors by Sarah Stern and letters by Jim Campbell. Each issue is basically a standalone story, mostly along the lines of Giant Days, so my assumption is that the hope was to do a few issues, assess, and then do more issues for years and years. That did not actually happen; subsequent Steeple stories have appeared on Allison’s webcomics site , so my guess is that the American comics market continues to Be Difficult.

As I said, both Billie and Maggie are pretty sensible , though they are in one of those weird Allisonian towns. I could wish for a bit more mania and craziness from both of them, to juice the stories up, but these are early days yet. These five adventures are quirky and fun, and the status quo gets upended pretty seriously at the end, which I hope will lead to odder, stranger stories for the next batch. So far , I’m counting this as solid B+ Allison, with signs that it could ascend to the top tier quite easily. And it’s entirely standalone, thus being a good entry point for new readers.

[1] Potential counter-argument: what about things like Bobbins and Scarygoround, which have larger casts around whom the plots circle? How do they fit into this schema? There I pull out a timeline, and argue that the count of Allison’s central characters for a given story tend to diminish over time, and so, therefore, in about 2030 he will publish a comic featuring no central characters!

Reposted from The Antick Musings of G.B.H. Hornswoggler, Gent.