Ed Catto: That Other British Invasion

One day in the early 80s, I was with my girlfriend in a shopping mall. Somehow I had been relegated to the role of sidekick while she shopped. I liked to do a lot of things with her, but shopping wasn’t high on that list. I was bored so I decided to buy a comic book to read while she shopped.

Back then I was enjoying a lot of comics and purchasing them every week at Kim’s Collectible Comics and Records. But one store in that mall had a spinner rack filled with comics, and I knew I could snag an issue that I had missed.

Back then I was enjoying a lot of comics and purchasing them every week at Kim’s Collectible Comics and Records. But one store in that mall had a spinner rack filled with comics, and I knew I could snag an issue that I had missed.

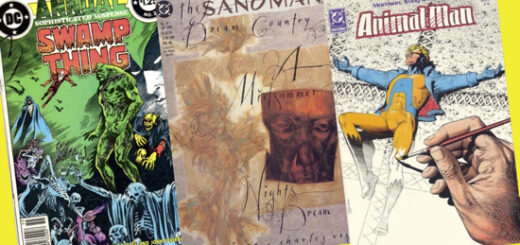

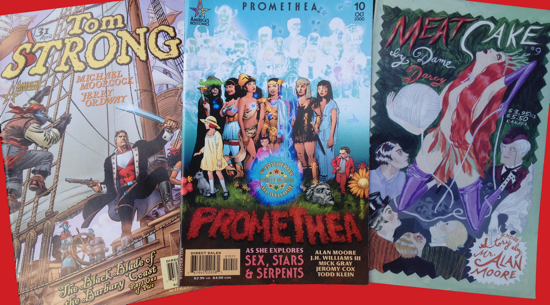

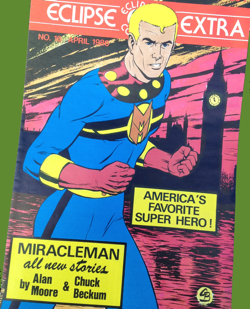

I evaluated the comics available on that rack and hoped that one would be my salvation from the dreariness of shopping. I reached out for Swamp Thing #21, and was surprised to find an unfamiliar writer wrote it. I decided to give it a try nonetheless.

Those initial low expectations quickly gave way to… my brain exploding! That issue masterfully took a fresh approach to a tired concept, and wrapped it in thoughtful, clever and creepy prose. It was a big deal. I was so excited, and at the same time so frustrated, as I couldn’t really discuss it with that girlfriend. She had no interest in comics.

I didn’t know it then, but comics were about to change.

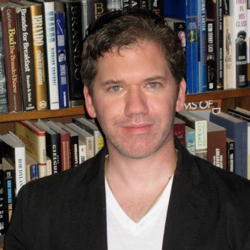

Alan Moore, that writer, was just one of the creators who ushered in a new era of comics. Sequart’s newest book, The British Invasion – Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, Grant Morrison and the Invention of the Modern Comic Book Writer discussed the important contributions of these writers. I was able to catch up with author Greg Carpenter and he shared some insights.

Ed Catto: Can you tell us a little bit about your new book, British Invasion, and what you set out to do with this book?

Ed Catto: Can you tell us a little bit about your new book, British Invasion, and what you set out to do with this book?

Greg Carpenter: I’d be happy to Ed, and thanks for having me here. The British Invasion is an in-depth analysis of the intertwined careers of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Grant Morrison – three influential British comics writers who first began writing American comics in the 1980s. The book traces their work from the ‘80s through today (or as close to “today” as you can get in the book-publishing world), and it focuses in particular on how these three writers redefined our understanding of what it means to be a comic book writer.

At least, that’s the dry, academic-y answer. As for what I wanted to accomplish, on the simplest level I think it was to try to answer the question that students always ask me: “Why have comics become so popular lately?” Obviously that’s a loaded question with lots of presuppositions, but the gist of it – that comics culture has moved from the outskirts of society to the mainstream – seems fair. And for me, the answer to that question leads directly back to the work of people like Moore, Gaiman, and Morrison.

I remember back in 2004 when I was sitting in a theater watching The Incredibles. Here – in a Pixar movie that didn’t really have to be all that smart or insightful in order to be successful – was a full examination of the wonder and the absurdity of the superhero genre, viewed through a real-world prism with real world consequences. Even though there had already been several superhero movies by that time – some of them quite good – what struck me was that Brad Bird seemed like the first filmmaker who had really “gotten” writers like Moore, Gaiman, Morrison. The thrill for the viewer came, not from the style of the costumes, the nature of the superpowers, or the threat posed by the villain, but rather from the momentary suspension of disbelief that comes when you realize – this is what superheroes would really be like.

I remember back in 2004 when I was sitting in a theater watching The Incredibles. Here – in a Pixar movie that didn’t really have to be all that smart or insightful in order to be successful – was a full examination of the wonder and the absurdity of the superhero genre, viewed through a real-world prism with real world consequences. Even though there had already been several superhero movies by that time – some of them quite good – what struck me was that Brad Bird seemed like the first filmmaker who had really “gotten” writers like Moore, Gaiman, Morrison. The thrill for the viewer came, not from the style of the costumes, the nature of the superpowers, or the threat posed by the villain, but rather from the momentary suspension of disbelief that comes when you realize – this is what superheroes would really be like.

That thrill, that feeling, that … sensation is far more rare than you might think, and I knew then that at some point in the future I wanted to try to show everyone why that feeling is so powerful.

EC: What’s your personal fan experience, and did you enjoy these writers when they burst onto the scene?

GC: I came of age at the perfect time. As a kid, my comics reading was pretty random – a smattering of superhero books and a lot of commercial tie-ins like Marvel’s Star Wars and GI Joe. By the mid-‘80s I was pretty heavy into DC’s Star Trek, but I kept seeing all these in-house ads about a book called Swamp Thing that was winning all sorts of awards. This was pre-Internet and I lived in the rural American South, so a person wasn’t going to find much comics journalism in the local Wal-Mart. My education came from those in-house ads. And if a house ad said I oughtta pay attention to a particular title, well, that carried a lot of weight with me.

GC: I came of age at the perfect time. As a kid, my comics reading was pretty random – a smattering of superhero books and a lot of commercial tie-ins like Marvel’s Star Wars and GI Joe. By the mid-‘80s I was pretty heavy into DC’s Star Trek, but I kept seeing all these in-house ads about a book called Swamp Thing that was winning all sorts of awards. This was pre-Internet and I lived in the rural American South, so a person wasn’t going to find much comics journalism in the local Wal-Mart. My education came from those in-house ads. And if a house ad said I oughtta pay attention to a particular title, well, that carried a lot of weight with me.

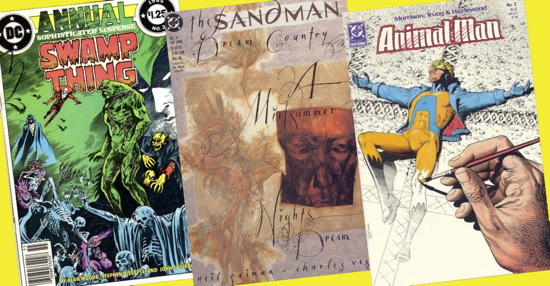

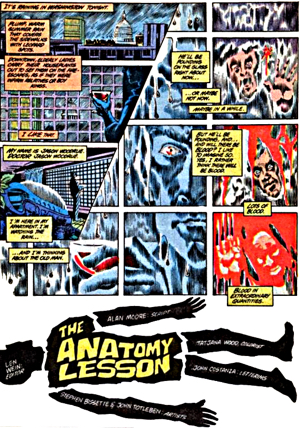

So I wound up buying Swamp Thing #56 – the blue issue. I didn’t really understand it, but I could tell it was different from all the other stuff I was reading. And once I started stepping out of my comfort zone, I found myself swept away with the energy of the times – The Dark Knight Returns, Watchmen, Maus, The Shadow, Byrne’s Superman, The Killing Joke, The Question, Black Orchid, Animal Man, Arkham Asylum, V for Vendetta … Sandman. It was an amazing period. And Moore, Gaiman, and Morrison were the ones shaping my worldview, my own personal mentors – priests, professors, and practical philosophers. They could do no wrong.

So when they drifted away from mainstream DC, I drifted away from comics. It’s hard to remember now, but in those days, in the part of the country where I lived, there wasn’t much access to books like From Hell, Sebastian O, or Signal to Noise. It was like loving music but only being able to listen to Top 40 Radio. So for me, it felt like my three favorite writers had largely left comics – even though they hadn’t. And I really didn’t care much for what had taken their place at DC, Image, and Marvel in the early ‘90s. So I stopped reading.

And then, as fate would have it, I was standing in a Wal-Mart and saw a comic book display. I paused for old times sake and was struck by a new title – JLA #1 – written by Grant Morrison. From then on it was like the Michael Corleone line – “just when I thought I was out, (Grant Morrison) pulled me back in.” And I’ve been reading ever since.

EC: You do such a great job of putting it all into context and telling a “big picture story.” As I’m reading your book, I’m thinking “Yeah, I vividly remember those stories from Supreme or Promethea.” I’m impressed by the way you are able to analyze those stories in the context of each writers’ career and within a particular historical timeframe. How much of a struggle was it to tell the tale that way and how did you go about it?

GC: You’re very kind to say so. I wish I could say that everything just fell together perfectly, but alas. I think the low point for me came when I was staring at dozens of little scraps of paper scattered across the floor, trying to figure out how in the world to make the overall structure for the book come together. I knew I wanted to do rotating chapters, but there were lots of organizational problems. While these three writers have always been active, their creative peaks often come at different times. So I was left with a floor full of jigsaw pieces that all came from different puzzles and all I had was an X-ACTO knife and some touch-up paint to try to make it all go together.

As for the rest, I learned to make a friend of the Grand Comic Book Database, tracing chronologies and sketching out long timelines. If I can’t see something visually, it’s never quite real.

EC: By focusing on these three British writers, are you leaving out other important creators that are important to the big picture?

GC: More than I could even begin to list. The beginning of the so-called British Invasion wasn’t even a writer movement – it was about artists. People like John Bolton, Brian Bolland, and Dave Gibbons had begun working for DC and Marvel and were doing great work before Alan Moore made a splash with Swamp Thing. And, of course, there were so many great writers in those early days – people like Alan Grant, John Wagner, Jamie Delano, Peter Milligan … and that doesn’t even begin to include the writers who came after these three – Warren Ellis, Garth Ennis, James Robinson, Mark Millar … you could go on and on.

And that’s just the British creators. The book focuses in particular on the impact of the Invasion on the notion of the modern comic book writer. If you want to really look at the development of the writer’s role, there are also plenty of non-British writers who helped pave the way for what these three were able to do. I’m thinking of Denny O’Neil, Chris Claremont, Steve Gerber, as well as writer-artists like Frank Miller and Howard Chaykin.

But ultimately in any book you have to focus. What is the problem you’re trying to solve? What’s the question you’re trying to answer? In my case, I knew I wasn’t writing an encyclopedia. I was looking specifically at the role of the writer, and these three writers’ work seemed so interwoven that it was impossible for me to talk about one without the other. But I still lose sleep over all the creators who frankly deserve their own book.

EC: I love the chapter titles. Can you tell me a little bit about how you chose them?

GC: I love that the titles worked for you. That was one of my earliest ideas for the book. Each chapter gets its title from the name of a song by either the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, or the Who. Some of those choices are hopefully pretty obvious – a Sandman-heavy chapter is “Golden Slumbers,” the chapter with Grant Morrison’s vision at Kathmandu is “I Can See for Miles,” and a chapter on Spawn is “Sympathy for the Devil.”

But beyond setting the mood or reinforcing the theme, the choices don’t follow any set pattern. I don’t think Moore, Gaiman, and Morrison correlate directly with the three bands – one of them isn’t the equivalent of the Beatles or the Stones, for instance – so I just drew liberally from all three to find the most appropriate title for each chapter.

EC: It’s a big book, but I’m sure you had to make decisions and choices about what to include. What do you regret leaving on the cutting room floor?

GC: When I started, I naively thought I’d be able to cover all the published work of each writer. It didn’t take long to figure out that was impossible. So there are lots of things I never got to write about. But of those things that I did draft and then take out, the most disappointing was probably a section I wrote on Alan Moore’s Neonomicon.

Any of your readers who’ve read that book know already that it’s a tough book to deal with – powerful, complex, and disturbing for a number of reasons. But when I was drafting the manuscript, I dove into it and wrote what I thought was a really nuanced, insightful analysis.

Well, have you ever had one of those moments of brilliance at 2 AM where you’ve just stumbled upon the plot to a novel that’s probably going to earn you the Nobel Prize for literature? You feverishly scribble the idea down so you don’t lose it, but then, the next day, when you pick it up to read it there’s nothing there besides the most banal idea imaginable. That’s basically the story of my Neonomicon analysis. When I found myself editing the manuscript a few months later and got to that chapter, I just scratched my head. What I thought was enlightening was utterly vapid. It was so nuanced that there wasn’t anything there. I thought about revising it, but the book was already overlong so I just dropped it. Maybe I’ll go back to it someday – just not at 2 in the morning.

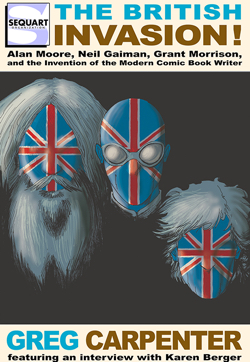

EC: We shouldn’t judge a book by its cover, but your cover is clever and to the point. How did the design come about?

GC: The cover is great, isn’t it? Kevin Colden, who has done some great work on The Crow among other projects, did the cover. In keeping with the theme of the British Invasion, it’s an homage to the album cover, Meet the Beatles.

But it didn’t start that way. Originally, I actually tried to sketch out an idea myself. It was an image of Mount Rushmore with Moore, Gaiman, and Morrison carved into the rocks. Trust me, it was even worse than it sounds. My wife took one look at it and said, “Seriously?”

So I went back to the proverbial drawing board and tried to draw an empty bandstand modeled after the Beatles, with a drum set, microphones, and three guitars. I sent this one to Mike Phillips at Sequart and he said something along the lines of, “Um … yeah. So, anyway … what would you think about something inspired by an album cover?” And with that, for the betterment of all humanity, I retired my drawing pencil.

Mike and I talked about several album covers, but we kept coming back to Meet the Beatles. For legal reasons, you can’t use a real person’s face on a cover, which is understandable, but (and I think this was Mike’s idea) we thought it might still work if we put them in Union Jack masks. And Kevin took it all from there.

EC: If you could go back in time and give any “Dutch Uncle” advice to Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman or Grant Morrison, what would it be?

GC: Oh, I don’t think they need my advice. They’ve each done pretty well on their own, don’t you think? So I dunno … I guess if I had to, I might tell them – especially Moore and Gaiman – to skip some of the work they did for Image Comics in the ‘90s.

But honestly, I don’t believe in second guessing the past like that. Let’s say, for example, you were able to help Alan Moore get a better Watchmen contract with DC, saving him from some of the nastier aspects of the profession. That would seem like a good thing. But would a happier, more content Alan Moore have gone on to write From Hell? I tend to doubt it. I don’t know about you, but given a choice between enjoying three years of Alan Moore writing something like Green Lantern – as enticing as that might be – or getting Moore and Eddie Campbell’s From Hell, I’m gonna take the Jack the Ripper story every time.

EC: There’s such a rich landscape of creative comics being produced today. What are you enjoying and what do you feel will be viewed as important in the years to come?

GC: It feels almost like a cliché to mention it, but I really love the March Trilogy. What’s special about it, I think, is that once you get beyond how amazing John Lewis is and how well he and Andrew Aydin have compiled his story, Nate Powell’s art is extraordinary. All too often, comics that are classified as “educational” tend to be stiff and lifeless – like your great-grandmother’s idea of what a “good” comic book might be. But Powell is the real deal. Great cartooning, imaginative layouts. The national media might make it sound like broccoli sometimes, but it’s really great comics storytelling. And because of its subject matter, it’s going to be part of the high school curriculum for a long, long time.

Among mainstream comics, I was a big fan of Matt Fraction and David Aja’s Hawkeye. I always joked that it felt like I was watching some mythical Quentin Tarantino movie shot in the ‘70s and starring Steve McQueen circa 1963. I also think Scott Snyder and Greg Capullo’s Batman is deceptively good. It’s one of those comic book runs that is easy to take for granted, but ten years from now we’ll still be thinking about it. And Eric Powell’s The Goon always makes me smile.

But the other area that makes comics exciting today is the changing demographics – particularly the infusion of more women creators and readers. Any time you can shake up the industry and change the aesthetics, good things can happen. I once got to interview the artist Janet Lee, best known for Return of the Dapper Men. She showed me some of her work in progress and, to be honest, I was dumbfounded. Instead of something conventional like rough pencil layouts, inks, or even watercolors, she was using a technique akin to decoupage, drawing and coloring images and then cutting them out and painstakingly layering them on a larger page. I can’t even imagine what it must take to do that, but once it’s published, her stuff looks unlike anything else out there. That’s what you get when you have greater diversity in the field – fresh voices, fresh perspectives, and new aesthetics.

In a lot of ways, that was the lesson of the British Invasion too, I think.

EC: What’s next?

GC: Well, my wife and I are both writers – her debut novel, Bohemian Gospel, was published last year by Pegasus Press (heavy-handed plug) – so we tend to alternate between projects around our house. That means that lately I’ve been doing a lot of copy editing and proofreading on her sequel, The Devil’s Bible.

That’s not to say I don’t have a couple of book ideas of my own brewing. I do. But I also remember what Hemingway said – the book you talk about is the one you never write.

EC: Thanks so much, Greg!