Mindy Newell: Happy @#$%&!! 2017

I am in an incredibly shitty mood. My mom had a stroke—well, not technically, but the results are the same and she ain’t doing so good. My dad is a soul trapped in a useless body lying in a nursing home. On top of that wonderfulness, last night I couldn’t get the pizza I wanted because my favorite place closed and my two fallbacks were closed—huh? Isn’t New Year’s Eve one of the busiest nights of the years for pizzerias?—so I ordered one from what seemed to be the only one open and it totally sucked, but I still pigged out on it. Pigging out on something you enjoy is one thing, but pigging out on something that isn’t really that good? Dumb, dumb, dumb. And also, unlike some people who eat when they are upset, I’m one of those who don’t, so why I wasted $10.00 on something I really didn’t want in the first place I can’t answer.

And then there’s the reality that in 19 days a man who is the most incompetent, the most dumbest (and please, no letters on my grammar), a man who is treacherously close to crossing the line to treasonous behavior—just what the hell does Putin have on him?—will become the 45th President of these United States. We are about to go from the classiest to the assiest.

Happy New Year?

I don’t think so.

Im-not-so-ho, we’ll be lucky to get to 2018 with our skins still intact.

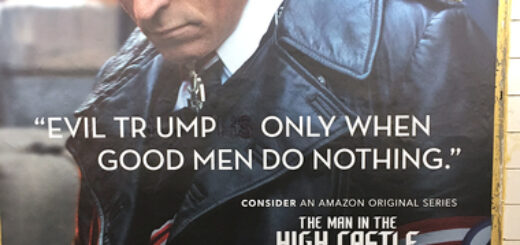

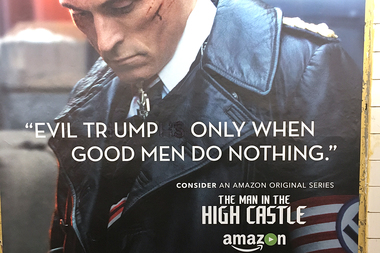

In other news, I recently finished watching Season 2 of [[[The Man in the High Castle]]], brought to you courtesy of Philip K. Dick (whose original book was published in 1962), Frank Spotniz (The X-Files), and Amazon Studios. For those not in the know, the premise of both the book and the series is: “What if the Axis powers had won World War II?” Well, that’s a simplification—there’s a lot more in there, particularly concerning not just alternate realities, but the nature of reality itself—but for the purposes of this column, it will do.

What is interesting—and somewhat depressing, as if I needed any more help in sliding down the ladder—is the reaction of some to the series, which, to tie it up with a bow, is: “Who needs a fictional fascist dystopia when the reality is already here?” I get it. Doing some research for today’s column, I came upon author (The Name of The Rose) and philosopher Umberto Eco’s 1995 essay, “Eternal Fascism,” in which he lists 14 “properties of fascist ideology.” I won’t list all of them—I suggest you look them up, if you have the stomach for it—but there’s enough here to make me shiver:

- Appeal to a Frustrated Middle Class: Fascism uses the fear of economic pressure from the demands and aspirations of lower social groups. Watch any of his campaign or “victory” rallies.

- Fear of Difference: Fascism seeks to exploit and exacerbate this…in the form of racism or an appeal against foreigners and immigrants. Muslim registry. A huuuuuge wall on the Mexican border.

- Selective Populism: Fascists use this concept to delegitimize democratic institutions they accuse of “no longer representing” the Voice of the People. “The media are scum.”

- Machismo: Fascists hold disdain for women and intolerance and condemnation of nonstandard sexual habits, from chastity to homosexuality. Grabbing some pussy, Trump? Or is she too fat?

- Contempt for the Weak: Remember when Trump made fun of the reporter who has a physical disability?

- Newspeak: Fascism employs and promotes an impoverished vocabulary in order to limit critical reasoning. Hello, Twitter, and a 40-character limit.

And here’s an example of some of the tweets that The Man in the High Castle elicited, courtesy of The Huffington Post:

Jack Shafer of Politico on November 21, 2016:

Donald Trump living high atop the Trump Tower or Man in the High Castle?

— Jack Shafer (@jackshafer) November 21, 2016

Emmett Hoops, teacher and linguist, same date:

Who needs The Man in the High Castle when America has already freely elected Donald Trump, our very own fascist?

— Emmett Hoops (@EmmettHoops) November 22, 2016

And my personal favorite, from Indiana University School of Public and Environment Affairs PhD candidate and Brookings Institute alum Dave Warren, on December 22, 2016:

Just got to that episode of Man in the High Castle where Donald Trump is elected President of the United State of America.?

— Dave Warren (@davecwarren) December 22, 2016

So the way I figure it is, that you should watch TMITHC on Amazon if you love Donald Trump because it will reinforce your faith in the marriage between politics and corporatism, or that you should watch TMITHC on Amazon if you’re scared of Donald Trump because it will reinforce your faith in the…what? The “It Can’t Happen Here” ideology? The “invulnerability” of our Constitution? The “It’s just a really good adaptation of a Philip K. Dick book” reassurance?

Happy fucking 2017.