Best-selling author Sir Terry Pratchett passed away on Thursday, March 12, and the final tweets from his Twitter account were a fitting and poignant way to announce his passing. Even though I knew it was coming, given Terry’s long struggle with Alzheimer’s and attendant health issues, it broke my heart a little bit more to hear that it really was the end.

I was fortunate to know Terry for almost ten years, beginning with my work on The North American Discworld Conventions after meeting Terry at a book signing in 2005 Along with being a great light in this world and one of my all-time favorite authors, he was also my longtime friend; and it’s hard to know how to sum up my feelings in the wake of his passing.

So much of my life would be different and much less rich without having known Sir Terry. From lending warmth and humor to the reading breaks I took from dry law school texts, to the experiences and wisdom and new opportunities I gained through building conventions from scratch, to wonderful friends I’d never have met if not for a shared love of Discworld, to all of the myriad ways his writing has caused me to ponder and question my views of the world, reading and knowing Terry literally changed my life, and I wouldn’t have it any other way. I know that I am not alone in my feelings here, and my sincerest condolences go out to Terry’s family, his other friends, and the many, many other Discworld fans who are also mourning his death.

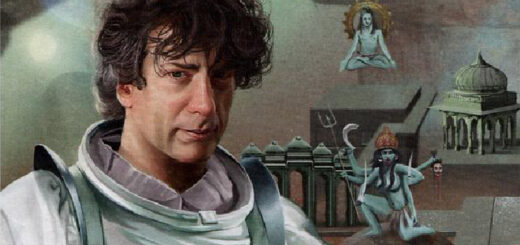

It’s both a nice thing and a strange one to see all of the public tributes to a person I am mourning on a personal level as well as due to the loss of his amazing talent; but I am very glad to see Terry getting the honor he deserves the world over for his achievements and contributions. Many are paying tribute to and writing about him and his works, and I’m sure that won’t cease any time soon, which is as it should be. It’s great to know that his impact on the world will be felt for years to come; and it’s comforting to read or listen to the social media posts and discussions by fellow Discworld fans and friends. (And this talk by Neil Gaiman, who honored Terry by devoting much of his time at an event onstage on March 12 to reading a bit of Good Omens and remembering Terry in conversation with Michael Chabon.)

Discworld fans are some of the most fun and intelligent folks I’ve ever met in fandom. As sad as I am over Terry’s passing, it delights me to see the many tributes, stories, and testimonials to how Terry and his work continuously changed people’s views and lives. It also surprises me not one bit to see that Pratchett fans have already begun to think up ways to ensure the memory of Terry lives on forever not just through his works, but through what his writing inspires other people to create. The “GNU Terry Pratchett” code is both a touching reference to Going Postal, and a bit of nerdy fan fun that would have delighted Terry, who was always glad to see fans enjoying Discworld, and unfailingly giving of his time and attention to those who appreciated his work.

But that doesn’t sum up the essence of Terry. The best summation of the Terry I knew comes from Neil Gaiman, in the foreword he wrote for Terry’s most recent collection of non-fiction writings, A Slip of the Keyboard. It can be read here. As Neil noted, Terry, while often genial, could in fact also be angry and impatient – with stupidity, with injustice, with unkindness – and he wasn’t one to hide or repress that anger. Instead, it underlies a lot of the genius that makes the Discworld series great. Underneath the humor and the fantasy, and the trolls, dwarves, wizards, witches, dragons, and more that inhabit that magical land, lie currents of deep and incisive observations and thoughts about how the world is versus how it should be if things were just and fair; and how and why we humans both often fail at being the better people he imagined we can be, and sometimes, against all odds, succeed in glorious fashion.

Terry’s brilliant satire both skewers humanity for its shortcomings and lifts it up for its goodness because of, as Neil put it, his love “for human beings, in all our fallibility; for treasured objects; for stories; and ultimately and in all things, love for human dignity. …anger is the engine that drives him, but it is the greatness of spirit that deploys that anger on the side of the angels, or better yet for all of us, the orangutans.”

This is the Terry that I treasure and will remember forever, from our first genial meeting in a small Virginia bookstore, through discussions and plans about what the North American convention ought to be like, (“by the fans, for the fans!”), and into odd and entertaining conversations had over a shared bowl of edamame at whatever sushi place we could locate wherever we happened to be. Along with his work, the funny and sharp yet still sweet moments I shared with Terry are what I will continue to hold dear. Like the story about the National Book Festival that I told BBC Radio 5live in the interview about 5 minutes from the end of this program. Or the time at the 2009 NADWCon when, after half a day of rushing around with Terry as his Guest Liaison, we found ourselves in the Green Room for a few unprecedented moments of calm. As Terry signed some books that needed signing, I took a pause from working at 2 p.m. to eat my first meal of the day, a yogurt and a granola bar (hey, I never said I acted like a sane person while running conventions). A couple of bites of yogurt in, Terry looked up from where he was industriously signing away and said, in a voice of concern, “Are you alright?” I said, “Yes, Terry, I’m fine. Why?” And he replied, with that slight twinkle in his eye, “You’ve gone quiet. That can’t be normal.” And there it was, the slyly sharp and observant Pratchett humor, poking fun at me for my regular stream of chatter, with which by then he was very familiar; but combined with a genuine concern that maybe something in the universe wasn’t quite right for a friend just then and something might need to be done about it. That was Terry to a T.

From start to finish, Terry was also defined by being a prolific and driven writer. Starting out as a journalist for the Bucks Free Press at the age of seventeen, Terry never stopped writing. Even near to the end, Terry continued to be driven to write, and has thus left us with one more finished Discworld book to look forward to; The Shepherd’s Crown, which should be out sometime this fall. It’s a Tiffany Aching book, which delights me both because Tiffany has always been a favorite of mine (Wintersmith sharing the title of My All-Time Favorite Pratchett Book with Night Watch), and because The Chalk where the Tiffany books mainly take place is closest in Roundworld geography to the area in which Terry lived. When I visited the area and walked out to Old Sarum and the surrounding area after reading the Tiffany books, I experienced the odd sensation of seeing The Chalk through Terry’s eyes and storytelling, and feeling the overlay of his magical fiction on the reality I walked through – or, to put it in more Pratchettian terms, feeling the thinning of the fabric of reality between the Discworld and Roundworld. For that experience as well as the beauty of the area and the feeling that, like Tiffany, Terry was very connected with and grounded in that land, The Chalk has always held a special place in my heart. I find it fitting that the last Discworld book is set in the Discworld equivalent of the land Terry lived in and loved.

In thinking of Terry’s passing, I recall that over the years, Terry noted that many people had told him that they feared Death less thanks to his portrayal of the character as an, if not exactly friendly, then at least comfortable and natural presence in the Discworld series. As with Terry’s other characters, Discworld’s Death reflects some of the fundamental truths about human nature that Terry understood and was so well-versed in; and is, I think, a Death Terry would not have been afraid to meet. It deeply saddens me to know that I will never again share a bowl of edamame and a fascinating conversation with Terry, but it comforts me to think that Death came for him as for an old friend with a mutual understanding of how the world works, and that they are now off somewhere together, keeping company with cats as they “murder a curry” during a companionable journey across the black desert to the ultimate end.

Although I can’t converse with Terry in this life anymore, the final thing I would like to say to him is: Even though you’ve left us, Terry, you’ll always be with me in spirit. I’ll miss you forever. Thank you for being my inspiration and my friend for so many years.

And when it comes to your writings, whether they be the much re-read favorites or the newest and last book of the Discworld series, I will always Servo Lectio.