Marc Alan Fishman: When the Words Come!

There’s no single moment in the creation of the comics that I make that cement the driving feeling of accomplishment more for me than finalizing the lettering on a page. When it comes time to build The Samurnauts, my studio (Unshaven Comics for the uninitiated) subscribes to a combination of the so-called DC Style and the so-called Marvel Method.

The DC Style such as its short-handed via various wikis and whatnot is a full script treatment. This means that the writers produce a script that outlines every bit of information to be in a given comic – from the panel descriptions, to the actual laid out dialogue, caption boxes, and onomatopoeia.

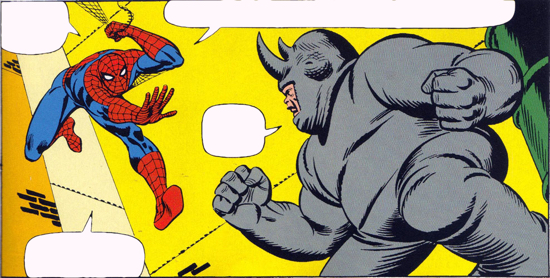

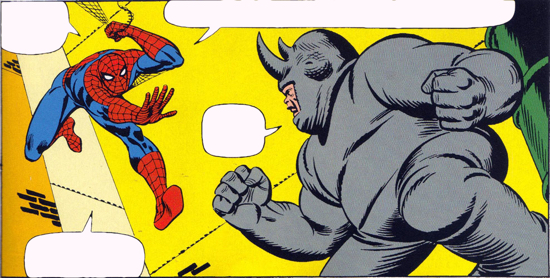

The Marvel Method is often the cited style of the stalwart staple of Marvel Studios, Stan Lee. Stan provided his artist collaborators the basic structures and story beats. He’d allow them to lay it all out as they saw fit. He then would come back to the final art, and add in all ‘dem fancy words.

To note: it’s likely in comics today that neither DC or Marvel actually adhere to these methods full-stop for the glut of writers they employ. It’s most likely down to individual preference, editorial management, or some combination of the two. And neither company originated these so-called styles.

Unshaven Comics utilizes both of these styles when it comes time to create an issue of The Samurnauts. Kyle Gnepper (resident writer and sales machine) is the full-script aficionado. As to why he prefers that style is an article I implore him to write on his own. What we’re here for today kiddos is to explore why I’m so enamored with the extemporaneous creation of the words that land on the page of the books that bear my name. Ya dig?

As I draw the pages, the script of my portions of The Samurnauts is always playing in my head like a Saturday morning cartoon. When we Unshaven Lads plot out an issue, we furiously take notes and debate on the outline. We create scenes, and story beats we want to hit on. We envision large set pieces, and tropes we want to pay homage to. When it’s time to translate those musings to actual actions? Well, for me, it’s all a matter of staring at a blank page and letting the story play out. I’ll layout panels (Adobe Illustrator is my medium of choice), and I’ll scribble near visually-illegible gestural drawings in the panels – my outline nestled in the margins of the artboard. From here, I typically bounce the final sketches to my artistic cohort Matt Wright. His keen eye for dynamic shots and action always set me up for logical-yet-exhilarating moments to capture in my final art.

By this point, I should make clear: my goal is to show more than tell. The immeasurably keen and kind Brian Stelfreeze once told me “A great comic book page can tell a story without a single word,” and I’ve long made what attempts I could to visually communicate as much as I could in the panel. This often translates to capturing my models with numerous poses, facial expressions, at different angles. My comic-making process is essentially a cartoon on mute for the first half of production. My end-goal always being to tell the entire story through the artwork first.

After the digital penciling, inking, flatting, and coloring, I’m left with a page ready for the final layer. Per the same conversation with Stelfreeze, I vividly recall him pointing out that “The words that appear on the page need not tell me what I’m already seeing. They need to fill in the gaps between the panels.” And so, with the page visually telling me one portion of the story, I add in my captions and dialogue in response to the action already on the page. With each blurb of text, I ask myself what am I communicating here that adds to the depth of the story? I’ll end on a recent anecdote:

On the first two page spread of the forthcoming The Samurnauts: Curse of the Dreadnuts #4 the action is clear as day; the Dreadnut dreadnaught (natch) reigns a hail of laser fire at the feet of the now-Delta-Wave Samurnauts, blowing them towards us (Power Ranger style!). Set in panels beneath the action we see their sensei, Master Al (the immortal Kung-Fu Monkey) imprisoned aboard their nemesis’ ship. We pull in on his pained expression.

When I outlined the scene, I knew that the action in the major portion of the page would not need to have a ton of dialogue – keeping in mind the sound effects of the lasers would be a key visual on top of the art. Pairing that action with the introspective moment by Master Al offered me the opportunity per Stelfreeze’s advice. The ability to counterpoint said action with narration that dives deeper into Master Al’s backstory (setting up Kyle’s five-page flashback on the following pages) becomes that thing that adds a layer to the artwork. By pairing reflective and solemn narration over the explosions creates a deeper experience – one I think that is best celebrated via the medium of a comic book. There’s no fancy star-wiping here, just a juxtaposition of incongruous actions that taken together tell us more than if they were presented more plainly.

And as I’d started saying at the top of this article, it’s here in these moments… when my unadorned artwork lays before me, I let Jesus take the wheel. Funny enough, I’m Jewish. I kid, I kid. Without a fully-developed script – paired with Kyle’s completed piece in front of me – I’m able to craft a more cohesive comic. One where my words set the table for Kyle’s, while still advancing the story in my portion of the book. It’s a balancing act that is the single most important selling point of The Samurnauts. Without that singular vision that marries the past to the future, our book is a mismatched mélange of wholly dissimilar action, save only for a monkey. Walking that tightrope, without a script to catch my fall is the kind of adventure that truly pays off when I’ve finished the last word balloon on the page and hit save. I reread the entire page, and play back the cartoon running in my mind. If it gels? It sells.

Excelsior, indeed!