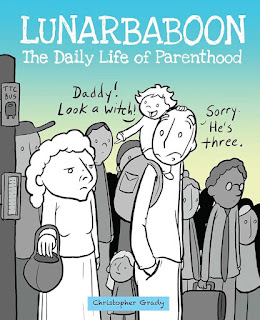

Lunarbaboon: The Daily Life of Parenthood by Christopher Grady

I fight with my tags, here on the blog. They tend to proliferate, with a core that I use a lot and a loose penumbra of things that I thought I’d use more often (Circles of Hell! Class War Follies! High Finance! Kids Today! Pedantry!) but just have a few random posts.

And there are areas where I keep thinking my one tag is too big and not entirely useful, but going back to re-tag would be insane. Such as Comics, a tag used on a full quarter of all the posts here. Clearly, that’s not doing its job. Breaking it into Webcomics and Masked Punching and The Smell of Newsprint and who knows what else would be more useful, but I know I will never, ever find the tens of hours that would take.

So, today, I have yet another comic. This one is a webcomic , and, as I seem to be saying a lot lately, I’m not sure if it’s still active. (That site throws the scary “not secure” warning in modern browsers, and the last comic was posted about a year and a half ago.) But there was at least one book, in 2017, which I just read, so it will live for the ages in at least that form.

The book is Lunarbaboon: The Daily Life of Parenthood , and, as is pretty typical for a general strip collected, it’s a somewhat thematic collection of the first two years or so of the strip. Now, I’m pretty sure Lunarbaboon – from what I’ve seen of it, here and there, over the last roughly a decade – was mostly about the main character’s relationship with his kids, but not entirely. This collection, as I think is the standard for a major-company series-launching comics collection (this is an Andrews McMeel book), wants to be easily categorized and grabbable, so it’s pitched as a companion to Fowl Language and Baby Blues and so forth.

Cartoonist Christopher Grady is more webcomicy than that, though: this isn’t a gag-a-day strip, but closer to a work of therapy. I get the sense Grady cartoons to make sense of existence, to understand his life and the world. So he has humor, but it’s not about getting to a joke – his strips are more ruminative, even mildly depressive, about fighting with sadness and feelings of unworthiness.

It can get a bit pop-psych for me sometimes, but it’s always honest, and I get the sense that it’s been useful for Grady – not just professionally, since he did it online for a decade and got a book out of it, but personally, as a way to contextualize the world and find an audience that sympathizes with his concerns and thoughts.

I guess I’m saying that Lunarbaboon is fun, and often humorous, but don’t go into it looking for Big Laffs. Go into it looking for the story of a guy who often feels overwhelmed by life – like so many of us, so much of the time – and how he copes with that, with the help of his family. And, of course, some of the crazy things his kids do, to either kick him out of depression or send him chasing after them to stop that crazy thing before something worse happens.

Reposted from The Antick Musings of G.B.H. Hornswoggler, Gent.