Martha Thomases: Every Picture Tells A Story

I have opinions about superhero comics that have no basis in anything other than my observations. There are no studies, no data, no proof whatsoever. But I have these opinions, and, quite often, reality supports them. Then again, quite often reality disproves them, but this column isn’t about that.

I have opinions about superhero comics that have no basis in anything other than my observations. There are no studies, no data, no proof whatsoever. But I have these opinions, and, quite often, reality supports them. Then again, quite often reality disproves them, but this column isn’t about that.

One of my core beliefs is that superheroes comics appeal to our inner two-year-old. That’s about the age when we realize that we have physical and mental limits, and we can’t shape the world to our whims. It’s natural that power fantasies attract our imaginations, because if we could fly and beat up any enemy and never get hurt, we could live the life to which we feel entitled.

This is also why teenagers like superheroes. However powerless you feel as a toddler, that feeling is dwarfed in comparison to how you feel when puberty hits. Now your body is not only able to do what you want it to do, but it’s actively working against you.

If you’re lucky – and you read good superhero comics, and you read other forms of literature and you have a good community for support – you will, while enjoying your power fantasies, begin to understand other points of view. I vividly remember stories from my childhood in which Lex Luthor found a world where he could be a hero. Through him, though looking at his face when he was finally cheered by people who loved him, I understood that each of us wants to be a good guy. We might disagree about what that means, but we are each the protagonist in our own stories.

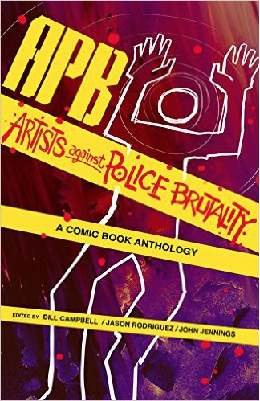

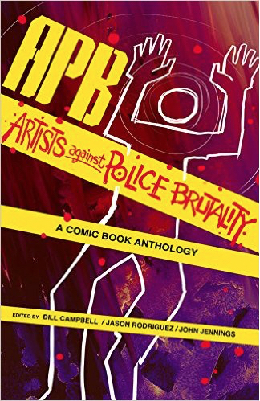

This is a really long and roundabout way to say that comics are an excellent way to learn empathy and discuss lots of opinions. The most moving recent example I’ve found is APB: Artists against Police Brutality, an anthology about the state of police violence and race relations.

The contents are brief essays and comics about police brutality. Some are to my taste and some are not. (Hint: Clear lettering might not be moody and atmospheric, but it’s legible and that makes a huge difference if you want me to read what you wrote. Rant over.) Some of the essays are a bit didactic and some are so personal and painful that I could barely get through them. Every one came from a place I’ve never been. Every one (even the ones I didn’t like) made me see the world in a new way.

I’m a parent, and, as a parent, my heart skips a beat every time the phone rings when my kid is away from home. When he was first starting to go out by himself, without my hand to hold when he crossed the street, I would make him call me when he got to his destination because otherwise I would worry that he was dead in a ditch somewhere. When he went to college, he almost went out to a ditch just so he could call me from there.

My worries are about drunk drivers or falling pianos or random lightning strikes. I’m not particularly worried about cops. As a white person, that’s not how I was raised. I expect the police to respect me and to watch out for me, my family, and my property. I understand, intellectually, that this is not everyone’s experience.

APB made me understand this difference viscerally. I could see how the police looked from the eyes of someone who is terrified, who is about to be beaten. I could feel the puzzlement and pain a person feels when a loved one goes out to run chores and doesn’t come back, ever. I could feel the shame and heartbreak of a woman whose brother grows up to be a cop who kills an unarmed African-American kid.

The book ends with a list of 881 people killed by police between December 15, 2014, and the date the book went to press on September 11, 2015. I can’t tell the race of each person, nor can I tell the reason he or she was killed.

I do know that each and every one had a story.