There’s a odd collection of graphic novels inspired by the Louvre museum, which has been running longer than I thought and has more books in it than I expected. Each bande dessinee is entirely separate; they’re all by different people with different plots, and seem to only have in common that they all involve the Louvre in some way.

There’s a

on Goodreads; I don’t know if it’s comprehensive, but it’s fairly long, at least.

And I read a few of the early books years ago:

by Yslaire and Carriere in 2014,

by Liberge in 2010, and The Museum Vaults by Matthieu in 2008. I don’t remember any of them well enough to compare.

Today, I just read Nicolas De Crecy’s

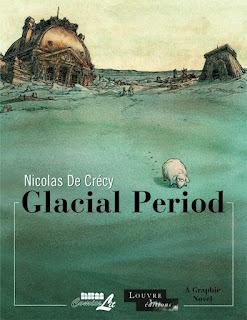

, the very first book in the “series.” It was originally published in French in 2005, translated into English by Joe Johnson the next year, and the current edition (no indications if anything is new or different, and I doubt it, having worked in publishing) came out in 2014.

My guess is that all of the books in this series are about “the power of art” pretty centrally, however each creator defines that. This one is, eventually, though it takes a long time to get there. It also has a pretty major fantasy element that just pops up almost two-thirds of the way through the book, which is somewhat surprising.

Glacial Period takes place – so it says – about a thousand years in the future, when a glacier covers Europe and has wiped out all memory of the previous civilization. This seems multiply unlikely – that there would be a new and completely unrelated civilization at the same tech level so soon after such a crash, that everything would be lost so comprehensively, that everyone would still be speaking European languages and seeming to be European people after that crash, and that what’s described late in the book as global warming would lead to whopping great glaciers in the first place.

Maybe global warming led to a series of devastating wars that killed most of the Global North really quickly, then the few survivors (perhaps in Brazil?) actively destroyed all records of the North, created some super-science cooling device that worked too well, changed their language to English, and went into a prolonged social crash, only to emerge recently? Oh, and bioengineered a race of talking dogs along the way, because why not?

The talking dogs are a definite, by the way: we see them, and one, Hulk (named after one of the important gods of the pre-glacial civilization, ha ha ha) is a major character here.

Also, there are a couple of panels that seem to imply how the catastrophe happened, only they make no sense. First, everyone got fat and lazy in the beginning of the 21st century. Then, global warming happened, really fast! (With a picture of the glacial landscape?) Only a few people “resisted” and fled South. There apparently was no one already living in the South to which they fled.

Frankly, I’m ignoring those panels, since they make no goddamn sense. I’m assuming they’re wrong somehow within the story, for a reason I didn’t figure out yet.

Anyway, there’s a scientific expedition across the trackless icy wastes of the forgotten northern continent – it is so forgotten than Hulk finds a coin marked “2 Euro” and this is a major discovery of their name for themselves. [1] There is some tedious interpersonal bullshit that doesn’t go anywhere or mean anything, but gives some slight characterization to a vague love triangle among the humans. (There’s one woman, whose father apparently financed and created this expedition, and the requisite one intellectual and one man of action both desire her.) There are some other characters – a few other humans, some dogs like Hulk – none of whom are important.

It’s not clear what this expedition is looking for, or how it’s looking. They seem to be wandering aimlessly, hoping to find something sticking out of the ice. They have no maps or documents from the Before Times, as previously noted.

Luckily, the author is on their side, so they do see a building sticking up out of the ice. No points to guess what that building is. Due to shifting ice and the needs of plot, the party is split, with Hulk alone deep within the halls of what he doesn’t yet know is a museum, and the woman and man of action similarly separate elsewhere in the structure for no good reason.

We also get a lot of panels of attempted anthropology based on the art – mostly a Delacroix gallery, I think – which is meant to be humorously wrong-headed, and gives De Crecy the opportunity to pop in a whole bunch of famous art into his book. (This seems to be the real purpose of the whole series, frankly.) This section is where we learn that our new civilization has absolutely no records of the vanished Europeans, which frankly seems completely disjoint with the fact that an entire museum of priceless artworks is still sitting, undamaged by time, under a protective snowball.

Anyway, then the fantasy element kicks in. I guess I have to explain it, though I should warn you that it’s just as random and bizarre as everything else in Glacial Period. You see, all of the art is alive. Or the spirits of the things painted live through the art? Something vague and muddy in between those two points, I think. All the art comes to life to talk to Hulk, to give the potted history that he so desperately needs, and to tell him that he has to save them from the imminent destruction of the whole museum.

Because all of this art can survive without any damage whatsoever for a thousand years, but there’s going to be a big ice-earthquake any minute now that will crush the Louvre and anything unlucky enough to be left within it.

Does Hulk do something unlikely and weird to save his entire expedition and all of the priceless artworks of the Louvre, leading them to safety across the ice? Of course. Does he do this in any way where the reader can figure out what is going to come out the other end of the saving motion? No. Not in the slightest.

Glacial Period is a weird book with muddy colors and baffling dialogue, set in a world that would contradict itself a dozen times if it made any sense at all. It is entertaining to read and full of great art by famous dead people, but I didn’t find it plausible for more than two or three panels at a time. Your mileage may vary.

[1] Belatedly, I’m coming to realize the core issue of Glacial Period: it’s of that classic genre in which only Europe is important, only Europe matters, and the world is essentially a blank canvas for European people to make their marks on. I’m more familiar with the derivative American version of that, where all the same but only European-descended Americans, who have kept the true germ plasm of the race alive within them, do all of those colonialist things and are the true lords of All Creation. (It’s bullshit either way, of course; I’m just pointing out the two strains, and maybe why I didn’t notice the older one as quickly.)