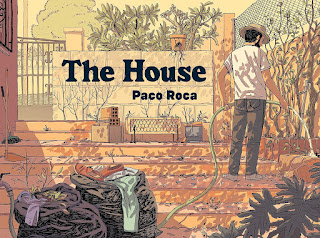

The House by Paco Roca

Some books have things that are easy to write about; some don’t. The more naturalistic a book is, the harder I find it to dig into – the more it’s just people living their lives, and the point of the book is seeing them, feeling some comparison to your own life, and making larger connections in your head.

A review can’t do any of that work for the reader. At best, it can point in interesting directions. At worst, it can short-circuit that process, making the book look facile and cheap and dull. Let’s see if I can find some interesting things to point towards, and avoid making vague windy claims.

The House is a low-key graphic novel, by Spanish illustrator and cartoonist Paco Roca, about three grown siblings – two brothers and their sister – over the course of a few weekends, maybe two or three months – which they spend, separately or together, in the vacation home their father built in their youth but which they haven’t visited much at all for several years.

That father died about a year ago; they’re cleaning the old place up to sell it.

That’s the story. That’s what happens. First Jose, the younger brother, with his relatively new partner Silvia comes to do some desultory clean-out – we see for ourselves that he’s the unhandy brother before the other characters tell us. Then the older brother Vicente, then sister Carla visit the house, to do repairs and clean things out. First separately, then together. They each have their own small cluster of family – spouses, children – and they bicker, in that comfortable quiet way families do, with each other over what to do with the old place and how to handle it and how good any of them are at specific things. They talk with their neighbor, an old friend of their father’s.

Behind all of this is, of course, their father’s death, and how they lived through it – what they did and didn’t do and how they reacted and who did what and who ran away and avoided what. There are no big revelations, but there are things they haven’t talked about before, things that they haven’t said to each other. There are things the reader will understand that the siblings probably don’t; we get a wider, more expansive view of the story than any of them.

Roca intertwines that with flashbacks, mixing moments across decades, using a muted palette of colors to indicate scene shifts and changes of emphasis. His short, fat pages – this book is smaller than an album, and in landscape format – often do more than one thing at a time, with scenes that sit side-by-side to comment on each other or that bounce back and forth from the past to the present.

It’s quietly magnificent, a universal story told precisely and well, using all of the language of comics to show this family in all their depth and complexity. Pages echo each other, colors indicate where and when we are, body language tells us what people are thinking and feeling, dialogue is natural and telling in both what it says and what it doesn’t. And, most importantly, it all comes together in the reader’s head: it’s the kind of story that shows rather than tells, that leads the reader on a journey without just throwing up obvious signposts for plot beats. Anyone who’s been in a relatively functional family will recognize a lot of this, and sympathize with at least some of the characters – if you have a sibling too much like Jose or Vicente, maybe not all of them!

One last note: I see I’ve neglected to mention the translator, Andrea Rosenberg, who is only credited in the backmatter. Obviously, the main body of the work is Roca’s, but all of the words in this English-language edition are via Rosenberg, and their strength speaks to that work.

Reposted from The Antick Musings of G.B.H. Hornswoggler, Gent.