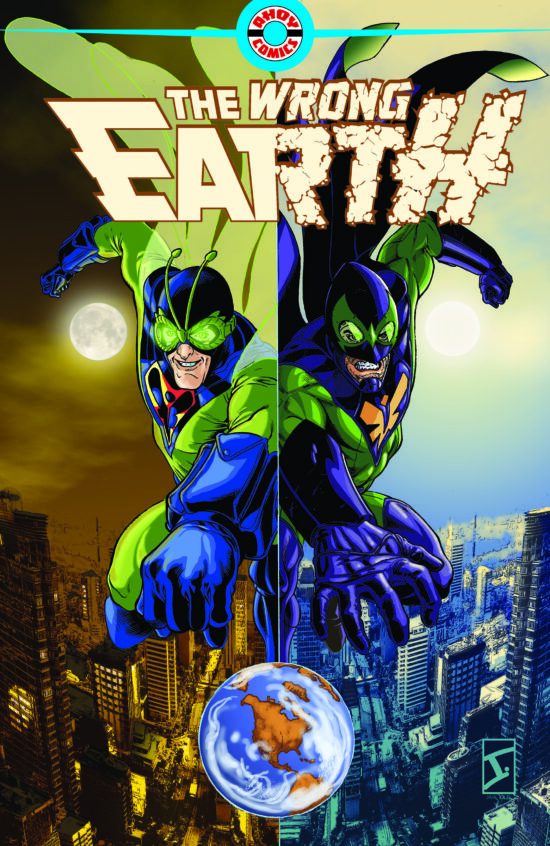

P/Review: “The Wrong Earth”

It’s exciting to be at the start of something. It’s especially exciting to be at the start of a new line of comics. Somehow comics, more than other forms of entertainment, have that feel of immediacy combined with a substantial tapestry of creative team-work. There’s always lots of dedicated people involved, and when they work together and make something new and exciting happen, it’s pretty special.

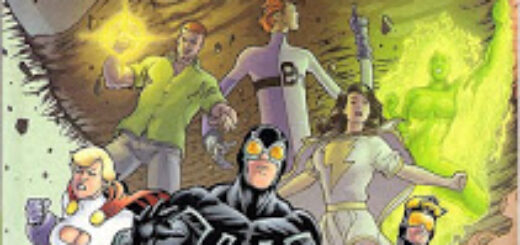

Ahoy Comic’s first new series, The Wrong Earth, is pretty special. And you can be at the start of it when issue #1 drops in stores tomorrow.

The new series offers readers a double-fish out-of-water story, as a classic Silver Age crime fighter changes places with a gritty “modern” hero. For superhero fans, there’s a lot to compare and contrast. And it’s done without any judgement on what type of storytelling is better. Writer Tom Peyer serves up clever new versions of old favorites, gently acknowledging the collective comic’s history that rattles around in collectors’ and/or fanboys’ heads. But he’s such an out-of-the box thinker that he will keep even the most jaded fans on their toes.

On the other hand, folks who aren’t overly well-versed in the nuances of fifty years of comic book heroes can enjoy this too. Anyone who’s seen one Marvel movie or one episode of a WB Superhero show is good to go.

Jamal Igle and inker Juan Castro provide solid art, often so smooth and skillful that you don’t even realize how good it is. Igle, as always, takes complicated scenes and makes them readable and engaging. He resists the urge to overdo it as he toggles between worlds, and what could have been jarring or tiresome is engaging.

One of the mantra’s for Ahoy is to provide a lot of material in each issue, and to ensure that it’s all diverse. The Wrong Earth #1 is overstuffed with creativity – including a prose story by Grant Morrison, a Too Much Coffee Man gag panel, a Q & A with Jamal Igle and a wonderful “lost” solo adventure of Stinger, the super hero sidekick.

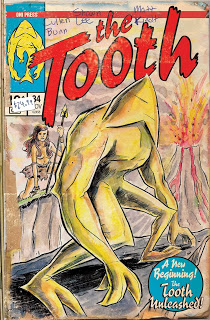

Paul Constant teams with SU professor and artist Frank Cammuso on the Stinger short story called “The Fairgrounds Horror”. It has all the charm and fun of finding an old comic in your grandma’s attic. There’s an astounding level of detail, and the yellowed pages really look like they are from a 1940s comic.

Ahoy Comics’ first comic, The Wrong Earth, is a promising start to new publishing enterprise. I’m hopeful retailers will support this book, and if your retailer doesn’t carry it, ask him to snag you a copy. You will both be happier for it.