Bob Ingersoll The Law Is A Ass #403

HAWKEYE’S TRIAL IS OFF THE MARKS, MAN

When is a murder not a murder? Give up? What say we find out.

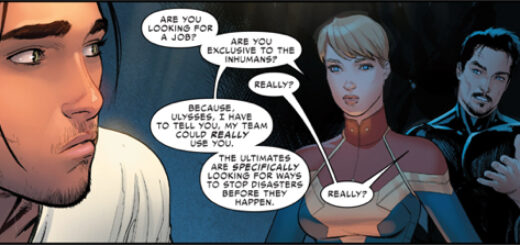

It all started with Ulysses Cain. You remember Ulysses Cain, don’t you? Inhuman who can predict the future and caused the whole Civil War II imbroglio when Captain Marvel and Iron Man disagreed over how he should be used. Lord knows I remember him. In Civil War II #2, Ulysses predicted that Bruce Banner would become the Hulk again and go on a murderous rampage.

So in Civil War II #3, Captain Marvel, Iron Man, and more costumed heroes than you can shake a double-page spread at confronted Dr. Banner in his secret lab. You can probably guess from the fact that was only part three of a nine-part story, the confrontation didn’t go as planned.

While all the heroes except one were talking to Bruce outside his secret lab, the Beast went inside and hacked into Banner’s computers. He learned Banner was injecting “treated dead gamma cells” into himself. (Interesting biology note: a gamma cell is a cell in the pancreas that secretes pancreatic polypeptide. Somehow, I don’t think those would have had any inhibiting effect on the Hulk. I think Beast meant to say dead gamma-ray-irradiated cells, but he probably didn’t have enough space in the word balloon for all that.) When Maria Hill, director of S.H.I.E.L.D., heard that Dr. Banner was experimenting on himself, she placed him under arrest.

Which made Banner angry. And do we like Dr. Banner when he’s angry? Who know? No sooner had Banner raised his voice than an arrow struck him in the head. Killing him. (Civil War II is over-achieving. It’s met its “Someone Has To Die Or It’s Not An Official Cross-Over” quota twice now.) Then Hawkeye revealed himself as the shooter and gave himself up.

Hawkeye stood trial for murder; in a sequence that jumped back and forth in time between prosecution witnesses, defense witnesses, and flashbacks so often you’d think Quentin Tarantino was the court reporter. Hawkeye testified that Banner gave him a special arrowhead that Banner had designed; one that would kill the Hulk. Banner told Hawkeye, “If I ever Hulk out again, … I want you to use that.” Banner asked this of Hawkeye, because Hawkeye was one of the few people Banner knew who would be able to live with the choice.

Hawkeye also testified that his eyesight was more acute than most people’s eyesight. That’s what made him such a good archer. He saw Banner was agitated and that his eye flickered green. He knew Banner was about to Hulk out and shot the arrowhead. (Hawkeye saw a green flicker in Banner’s eye from his perch up in a tree that was more than one hundred yards from Banner? That isn’t just acute eyesight. That eyesight is better looking than a super-model.)

In Civil War II #4, the jury found Hawkeye not guilty. How did the jury reach that verdict and find Hawkeye’s murder not a murder? I think we can safely eliminate the persuasive powers of Henry Fonda. So what did sway the jury to vote not guilty? Let me count the ways.

One: the jurors believed Ulysses’s prediction that Banner was going to Hulk out and kill someone. So it found that Hawkeye acted in self-defense. Two: they could have found that because Banner asked Hawkeye to kill him it was a mercy killing. Three: they could have found that they didn’t care that Hawkeye was actually guilty, the world was better off without the Hulk and they weren’t going to punish Hawkeye for killing the Hulk. That last one would be what we call jury nullification; a jury finds the defendant not guilty despite the defendant’s actual guilt for some sympathy reason. Juries aren’t supposed to do that but some do. And when they do, it’s still a valid not guilty verdict even if the reason is invalid.

The jury could have found Hawkeye not guilty on any one of those theories. Or on any combination of those theories. Juries only have to be unanimous on their verdicts, not their reasons for the verdict. So if eight jurors believed self defense, three believed mercy killing, and one believed in jury nullification; it was still a valid verdict, because all twelve voted not guilty. Hell, a juror could even have found Hawkeye not guilty because the juror believed the costumes some artists forced Hawkeye to wear through the years was punishment enough.

So there you have it. When is a murder not a murder? When it’s self defense, a mercy killing, or a jury nullification. Of the fourth way, which is the way I think really applies here: a murder is also not a murder when the plot needs it not to be a murder.