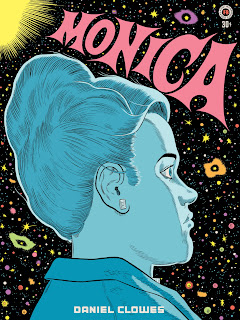

Some cultural artifacts are so rigorously assembled that one hesitates to criticize them, expecting that the answer from the trufans will be something like “well, but you see, the figure at the top left of the back cover is obviously there to explain your complaint, and you are a churl for missing that, and therefore all of your complaints are invalid.” But here I go anyway.

The figure at the top left of the back cover, by the way, is a satyr. There isn’t one in the book itself. This is clearly A Clue. But this is the kind of book that makes you tired of Clues long before you reach the back cover.

was Daniel Clowes’ new graphic novel for 2023; he reportedly had been working on it for five years, roughly since

. It’s told in nine chapters, all of which have Clowes’s standard mature art style but which diverge greatly in voice and tone. They also, I think, don’t all take place on the same level of story: I originally thought it was alternating the “real” story with in-story fictions, but it’s not quite that clear or obvious. My guess, as much as I care (which is frankly not much) is that three or four of the chapters are stories told by the title character, though it’s not clear when she told these stories, to whom, or why she wrote them within the confines of the overall story.

Bluntly, those chapters are horribly overwritten in a clanking style. I think this is deliberate on Clowes’ part – but it also calls the reader’s attention to the fact that even the “well-written” bits are overwritten, over-narrated, and overcooked. Clowes has always been a creator who loves extremes and trashy genre elements, but I don’t think it was a smart thing to call attention to his overwriting in a book as overwrought as this one.

Monica is the main character, and our wordy narrator. The book covers her whole life, in leaps and bounds, plus those digressions that I’m going to take as her (mentioned once, never important) adolescent attempts at fiction.

Before I go further: I will run through each section of the book. There will inevitably be spoilers. I do not recommend this book for anyone other than those who enjoy watching train-wrecks in slow motion. Take all that into account if you read on.

We start with “Foxhole,” in which Johnny and Butch, two footsoldiers in what we realize later is Vietnam, talk in a massively self-consciously doom-laden way for three pages about their lives, philosophies, the specter of imminent death, and how everything must be going to hell back Stateside. This has the tone of the later “fictional” pieces in Monica – overwrought, clunky dialogue and all – but I suspect it’s meant to be part of the “real” narrative.

Smash-cut to “Pretty Penny,” where we open with Johnny’s fiancé having just fucked some other guy – he’s Jewish, which I suppose is supposed to make it worse? They also talk in a patently ridiculous way: even dull readers should realize by this point that this isn’t to be taken seriously, that it’s dialogue reconstructed much later from someone’s slanted perspective.

That fiancé is Penny, who, in the much later words of Elvis Costello, doesn’t know what she wants, but wants it now. We soon learn we’re hearing her story told by Monica, who is born almost three years later (assuming we start in the late ’60s, that puts her birth somewhere around 1969-1972) – and that may be why it’s sketchy and random and why Penny comes across as an unknowable ball of anger, reaction, and spite. This section is about twenty pages long, getting Monica to about the age of three, when Penny – after a pinball round of boyfriends and apartments and random caregivers and emotional explosions – dumps Monica with her own parents and disappears forever.

Next we get the seemingly unrelated “The Glow Infernal,” a vaguely Lovecraftian tale about a young bowl-cutted man in an ugly purple suit who returns to his childhood town to find it controlled by blue-skinned people of vague origin. He quickly joins the resistance and is instrumental in their downfall, but is transformed in the process – very literally.

Monica returns to tell “Demonica,” the story of how she fell apart during college when her grandmother died suddenly. She holed up in a lake cottage, talked to no one, and claims to have communed with the spirit of her dead grandfather through an old radio. At the end of this period, she has a car accident that puts her in a coma.

By this point, the reader may wonder if Monica is a reliable narrator. I don’t think that’s the direction Clowes wants the reader to go, but if one assumes she’s prone to psychotic breaks (perhaps like her mother?) that’s one way to interpret the story.

“The Incident” is another story written by Monica, I think, in which a version of her father is some kind of detective or fixer, bringing a young man back from bad companions to his family, only to find (yes, again) something unexplained and maybe inexplicable has happened to the town, so he has to flee with his charge.

Monica wakes up from her coma for “Success,” told from a viewpoint twenty-two years later. (Note: that is not now, and not the frame story for any other section. Every section vaguely hints at being a document from a particular time-period, without ever making that clear or doing it believably.) She started a candle business after a few years of recuperation from the coma and then the usual youthful dissipation, but has just sold that business for a small fortune. She’s now getting obsessed with finding Penny, and learning the truth about her mother – but gets sidetracked by a pamphlet from her childhood from a nutty cult.

“The Opening The Way” continues that story, with Monica learning about the cult (which schismed into a blandish New Age convention business and a hard core of the really loony ones) and then, inevitably, joining it and getting caught up in its horrible philosophy, unpleasant people, and grungy surroundings. She gets out in the end, still not having found Penny.

And then we get “Krugg,” which is probably another story written by Monica – this late in her life? who knows – in which a painter monologues tediously as a blatant stand-in for the father Monica never knew (and who she sought in the crazy cult just before).

Last is “Doomsday,” in which an aged Monica, in what seems to be the present day or near future, explains how she did find Penny – who was old, and more than a little unhinged, and didn’t give Monica any real insight before she died – worked through her problems with a therapist over a number of years, met a nice man that she might be able to have a relationship with, and finally found her father, who was a bland old man who also couldn’t give her any real insights into herself.

Oh, yeah, and then she unleashes Armageddon in the last panel, because why not?

Um, OK.

I have to assume Clowes means that literally, and thinks that he has constructed his story to lead to that point. I didn’t believe it at all, and didn’t see even the kooky cult teachings as really leading to this particular apocalypse. (There’s a demon-figure in the cult’s mythos – if he appeared to Monica, that would be one thing. This is something entirely separate.)

My working assumption is that this is another sour Clowes story, about how all of humanity is sordid and corrupted and horrible. But I took it as a story about one woman with serious mental problems, who tells us the entire story but, in the end, can’t be relied upon at all.

I can’t recommend this at all. It’s longer than it looks, it’s full of bad writing – most of it on purpose, I hope – and doesn’t say anything new or interesting for Clowes. It’s just a confusing, kaleidoscopic wallow in his typical misanthropy, without anything new or special to redeem it.